Harold Varner wants change, not confrontation in his quest for more diversity in golf

"As Harold Varner's upcoming 30th birthday innocently marks the shame of Shoal Creek, has the phrase 'black lives matter' plunged golf into a state of self-examination and soul-searching?"

Monday 29 June 2020 09:10, UK

As we approach the 30th anniversary of Shoal Creek admitting its first black member following protests ahead of the 1990 PGA Championship, David Livingstone celebrates Harold Varner's ambition to improve diversity in golf...

Harold Varner III, the only African-American on the PGA Tour, is in Detroit this week, a city where black lives have always mattered and where Martin Luther King previewed his "I have a Dream" speech before heading to Washington in 1963.

There is a powerful link, too, between the city's black population and golf.

Detroit was home to the great boxing champion Joe Louis who probably did more than any other American sportsman to fight racial discrimination and who used his latent ability as a golfer to help remove the PGA of America's colour bar.

Louis received an invitation to play in the 1952 San Diego Open but the sponsors were reminded of the PGA's "Caucasian only" clause by President Horton Smith, a man of some standing as winner of the first and third Masters tournaments.

Unsurprisingly, an ill-tempered face-to-face meeting between Smith and Louis resulted in a technical knockout with the heavyweight champion being allowed to compete as an "invited amateur". The "Caucasian only" clause was not revoked until nine years later but the stand taken by Louis undoubtedly paved the way for generations of black professionals to come.

It also made Detroit love the champ more than ever and, this week, in a city of such rich, black tapestry and in the continuing aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, Varner will be conscious of his profile and influence. Besides, a personal timeline gives Varner his own connection to the rights of black golfers.

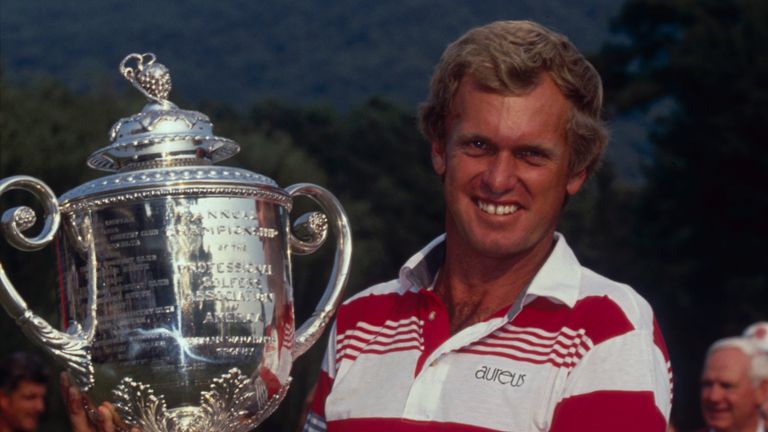

He was born three days after the infamous PGA Championship at Shoal Creek, Alabama, in 1990, when national outrage over the club's racist policy forced golf into another significant change. In the build-up to the championship, Shoal Creek's founder Hall Thompson was adamant the club would remain white-only, stating defiantly: "This is our home and we pick and choose who we want."

The PGA were, at first, reluctant to get involved, saying it was not their problem, but when sponsors and advertisers began to pull out, they pressured Thompson to give in and he reluctantly made a local African-American businessman an honorary member.

Before Thompson's climb-down, if that same businessman had turned up at the club, he'd have been handed a set of keys and told to park a member's car.

Get the best prices and book a round at one of 1,700 courses across the UK & Ireland

Even today, prejudice still lingers, but the scandal of Shoal Creek all those years ago was instrumental in changing the image of professional golf because each of the game's governing bodies agreed never again to play tournaments at clubs with an all-white membership policy.

In the three decades since, golf's ruling organisations have continued to broaden the game's reach by pledging the same rights to women and by opening the door to major championships for golfers of all colours and creeds from all over the world.

So why now, as Harold Varner's upcoming 30th birthday innocently marks the shame of Shoal Creek, has the phrase 'black lives matter' plunged golf into a state of self-examination and soul-searching?

The answer, of course, is glaringly obvious, Varner's solitary African-American presence on the PGA Tour is a stark reminder of how little diversity there is in a game that, even in South Africa, prompted a headline two years ago which asked: "Why is Golf so white?"

Varner, himself, says it starts not with discrimination but lack of access. "Any time that someone wants to be great at something, they have to have the opportunity to experience it, learn how to get better. It's just so expensive to play golf, and that's the problem, to be honest with you."

His words certainly ring true here in the UK where we have the same problem with black and minority groups who are culturally and economically distanced from a game like golf, just as many white, working-class kids have been too. The exclusive nature of the game over the years has closed the door on many a potential golfer who had neither the means nor the opportunity to play.

More than that, it was not a welcoming sport. Anyone who regularly passed the entrance to golf clubs back in the 1970s or '80s would be familiar with a warning sign saying "Private".

Yes, much has changed and almost all clubs have opened their gates to paying customers but it's not been for entirely altruistic reasons. Their need to pay the bills has ticked a box for access but it only applies to those who can afford the green fee.

Which takes us back to the life of young Varner when he was growing up in North Carolina. "I had nothing," he said. "No nice clothes, no lights, and, hell, sometimes no buck-fifty to eat lunch in high school."

What he did have in his life was a then-unknown fleeting brush with sporting destiny because, remarkably, he had been born in the same hospital in Akron, Ohio, as Steph Curry and LeBron James. At an eventual 5ft 7ins, Harold was never going to follow his illustrious elders into basketball, but the stardust he picked up in that maternity ward in Ohio stuck with him in his family's move to North Carolina.

He reflected on that when he penned an open letter after the murder of George Floyd in which he expressed his anger and disgust at "evil incarnate" but balanced his bitterness with gratitude for being so lucky as a youngster.

He said: "The people who pushed me to succeed were old white and black men at my local muni. They were the ones helping me with clothes, bills, and food. The white guys aren't racist, and the black guys aren't either."

Varner's letter went on to say he will always support African-Americans subjected to racism and he'll do the same for all ethnicities. It also said: "Life is more nuanced than just a simple statement, and if there's one thing that is emblematic of today's society, I think it's that we constrict ourselves to single-minded thought."

You get the sense that Varner, like his idol Tiger Woods, is careful to steer a course towards change but not confrontation, even if it leaves them both open to criticism from activists who demand more radical action.

In golf, radical is a word that rarely crops up, so within the confines of a tightly-structured sport how do you get more black and minority ethnic kids playing the game and perhaps becoming stars of the future?

It's a question that's been asked a million times and I'm sorry to say that, despite the many admirable initiatives in the UK through the Golf Foundation and in the USA through the likes of the First Tee Programme, nothing's changing fast.

That's not to say golf is not growing. In Asia, for instance, there's a production line of exciting young players literally changing the face of golf but, within their own countries, they are not from minority backgrounds and none of them, for sure, will be hailed as a slumdog millionaire from Mumbai.

Back here, in the old world of golf, breaking down the barriers of the restrictive club culture in golf and spreading the word in schools that golf is a healthy life-long sport is the obvious way forward, but there are so many economic and social issues that stack up against inner-city kids.

I'm not sure that targeting specific ethnic groups is the right thing to do but, in any case, I'm left with the question of whether the young people in those groups really want to play golf. Are there enough black kids in America who want to be Tiger Woods rather than LeBron James? In the UK, which youngster from the same background wouldn't prefer to be Raheem Sterling or Marcus Rashford or Tammy Abraham?

The simple fact is golf has to be realistic and remember it's asking minority groups to take up a minority sport that's slow, expensive, and complicated when, naturally, they're drawn to the speed and glamour of the Premier League in England and NBA in America.

It's a dilemma that calls for patience and the sure and steady removal of any remaining obstacles. Golf needs to stop looking down its nose at people who don't look the part, people who make us uncomfortable simply because they look or dress or speak differently.

Imagine a young, scruffy, tousle-haired Harold Varner walking into your club and how you'd feel. It's maybe a troubling thought but it's one we probably need to have. Harold hasn't forgotten those days as a young boy when his local course gave him a $100 all-summer deal and the old guys at the club, black and white, helped him out with clubs and food and clothes.

Now his Foundation, in turn, is helping the next generation. One line on its website says it all: "HV3 Foundation is providing affordable access to youth in sport."

Bravo Harold.