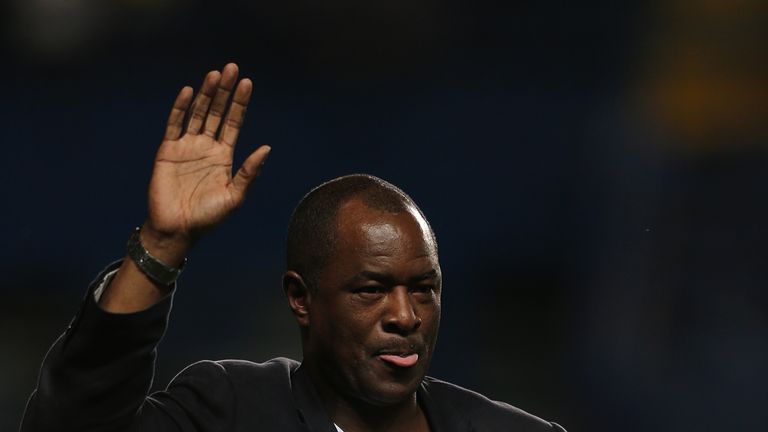

Mental Health Awareness Week: Paul Canoville on depression, addiction and racism

Chelsea's first black footballer gives a frank account of his extraordinary life as part of Mental Health Awareness Week

Thursday 11 August 2022 10:43, UK

As part of Mental Health Awareness Week, former Chelsea midfielder Paul Canoville writes candidly about his experiences of depression, racism and addiction.

Chelsea's first black footballer, Canoville suffered racist abuse on the pitch before his career was cruelly cut short by injury at the age of 25.

Then came a battle with drugs and two bouts of cancer, but here, in a frank first-person account of his life, Canoville explains how opening up in counselling gave him the tools to get his life back on track.

Canoville, now 56, played 103 games for Chelsea in a five-year period between 1981 and 1986. He was signed from non-league Hillingdon Borough in December 1981 and went on to play for Reading, but a serious knee injury ended his professional career at the age of 24.

Now, The Paul Canoville Foundation helps young people facing economic, physical or mental adversity to build life skills; his mission is to inspire and equip young people to overcome challenges through the use of sport. Paul seeks to teach young people they do not have to go through problems in silence or alone, and gives them life skills to build their resilience and confidence.

Warning: Explicit content. Some readers may find the content offensive or upsetting

_____

People would ask: "Do you miss football?" and I'd say: "Nah, of course I don't."

But I was dying inside. I lived to play football.

The love of football was taken away swiftly, at the age of 25. I was in denial. I had a drug problem after leaving the game. I was depressed.

I wasn't alright, but I didn't want to let people know I wasn't alright. It was that stigma of telling people. Those situations, where you see men taking their lives, I always saw it as being weak. But, believe me, I ended up trying.

_____

Coming from the first generation of Windrush settlers, by way of culture you didn't share your problems. Back then, if you have a problem at home, it doesn't leave the four walls. But I didn't even share them with my mum. I kept it to myself and it ate me up.

Mum was disciplined, she wasn't that loving, affectionate woman. I was scared to even think to say to her: "Mum, something happened at school." I wouldn't tell her, I'd keep it in.

I love football. But it wasn't coaches and scouts I wanted to impress, it was my parents. Dad left when I was a baby, and mum didn't take football too seriously. I'd come home with man of the match awards, and I'd want to share it with my mum. But she'd bring me down.

"Go and do your chores!"

I needed an older father figure, or an older brother, to share issues with.

I bunked off school a lot in my early teens; in one term I'd taken 75 days off. I spent time in Borstal for a silly burglary, and it was embarrassing. We broke into a shop, the police came around and we were hiding in these bushes for an entire morning. We decided to get up, walk about, pretending we were heading to work. The police came by and started to stop near us, and when they stopped, we stopped. That made it obvious. I never grassed the others, and they gave me four or five months.

Borstal, Christ. I'd never been locked up like that, where my privacy was literally taken away from me. It hit me hard. Military-style enforcement.

I came out and thought: "Nah, this is a place I do not ever want to be in again." I started taking my football very seriously. Mum had lost interest in me at this time, but Chelsea came in, I got a trial there, and it all began when I was 19.

Signing that contract was the best day of my life. "This is it, this is where I belong."

_____

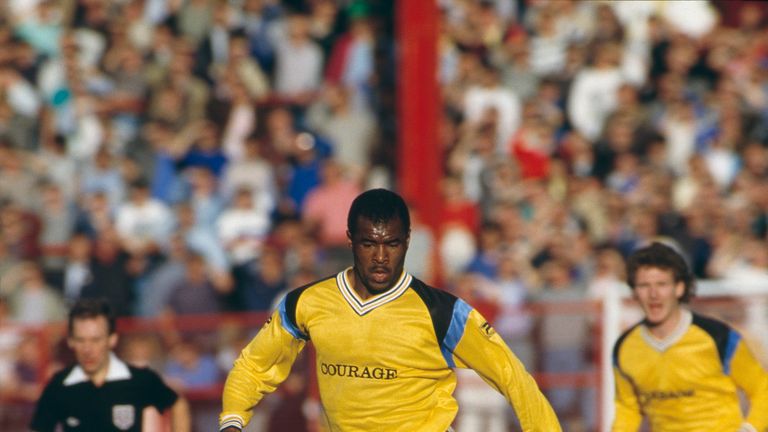

I loved the reserves, and was thinking: "This should be different quality to non-league," but it was so easy. I was scoring for fun, right, left and centre. In non-league you were kicked left, right and centre. Within four months I was in the first team.

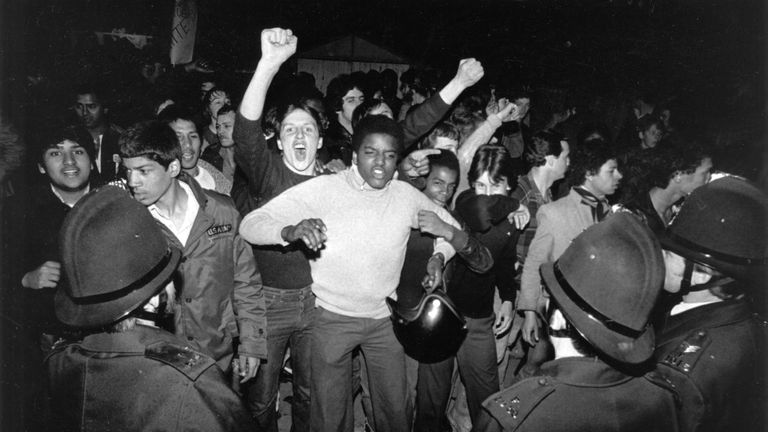

Before my first game against Crystal Palace at Selhurst Park, I was over the moon. I told everyone to come down and watch.

I'd experienced racism in Southall where I grew up. The National Front were rife in that era. It was frightening, and if I wanted to go outside, I had to take my sister with me.

If you saw a car drive past and then see the red brake lights as if it is slowing down, you'd do a U-turn on foot, and have to go around the long way, because you know that's a bunch of white boys coming out to get you. So I'd grown up with that.

But now, I'm at Selhurst, not thinking about that. This can't be in the pro game, surely? They were calling me golliwog, shouting: "Go home!" and throwing bananas. All the time I'm thinking: "These Crystal Palace fans are really trying to put me off." Stadiums were so close at the time, you could hear everything.

I turned around to see it wasn't Palace fans.

It was my own fans.

I was stumped. It hurt.

I didn't even know I was the first black player to play for Chelsea. At home and away games, you'd be called a n****r.

My first goal was against Fulham at Craven Cottage in April 1983. I'm so excited at scoring my first goal, but it wasn't accepted by some fans. Why? Because I'm black. I was so confused. I always had this feeling I had to play twice as well as my team-mates to be accepted by my own fans. It spurred me on.

I used to go and warm up down the east side at Stamford Bridge, and there was a big green behind the goal to go and stretch. They'd shout racist abuse at me. "Go home!" I'd be over-stretching behind the goal, the bench would be shouting: "Canners, come here!" but I'm pretending I don't see them. I don't want to walk past that East Stand again.

I'd get the tube to the game, come out of Fulham Broadway with my cap on not to be seen, and National Front would be outside of the tube stop handing out leaflets. After the game, I'd wait two or three hours until after the game until the crowd died down because I was scared.

Don't get me wrong, there were some very, very supportive fans there, when they saw what I could do. Through all of this, I didn't look at the fans negatively. I was humble about where I was, it was my opportunity and my dream, and there was no way I'd do anything to jeopardise it with any anger.

That may have been my downfall. I didn't complain. They'd think I'm too weak, so I bottled it up.

_____

In 1986 I joined Reading. After 12 games of the season, we were doing alright and the boys were great. We were third from the top, and we went up to Sunderland.

A corner came over, David Swindlehurst was close behind me, I let the ball run past me, turned, and he took my right knee. The weight took my knee one way with my foot planted on the floor. I didn't realise the extent of the injury. I was on the ground, my team-mates kept holding me down and I wanted to get up to take the free-kick. I saw it was dislocated, my knee was one way and the leg going the other way. I woke up the next day with the leg in a cast.

I said to the doctor: "When will I be back playing?"

He's told me straight: "Son, this is the worst injury in football. Dislocated knee, torn ligaments, and your cruciate is gone."

I felt beyond low.

My mum straight away wanted me to find another career. But how? I had nothing behind me, skills-wise. I didn't even go to school.

There was a whole year of rehabilitation to build the knee up. My first game back against Bournemouth, I kept protecting my right knee, going in with my left. A tackle then came in, I had to take it with my right leg, and at first I thought it had gone OK, but it had swelled up like a balloon. Reading were straight: "Paul, we're not going to renew your contract."

I took the settlement payment, went home and thought: "I'll find another job." But you're not used to 9-5, you're used to 10-12 and that's it. I was completely lost. Now I think: How was there not help from the FA, clubs or support groups for when things like this happened?

I didn't want anybody to know outside of the team to know I had a problem. Not one soul. We were footballers, people idolised us.

_____

I didn't even know I had depression. I felt down, and didn't know what it meant. I had to find work, but I was still living the golden life.

Football becomes your life, and you live that same lifestyle.

I was going out partying in the night, coming back at 3am. I'd found a job as a delivery man, and started at 5am. At times I didn't even sleep after partying, I went straight to work. I could have killed anybody. I'd call in sick a lot of the time, and did it so often they released me.

Then came the drugs.

I thought: "These drugs can't control me, it's just fun." I wasn't into drugs before. It was given to me, I didn't know what it was, I took a puff, and it smelt funny. I said: "What is this?" It was crack cocaine. I said: "Are you mad?" and passed it back. At this point, I'm looking for the side-effects, but then I'm thinking: "This is alright…"

Then you start dabbling.

Crack cocaine was an enhancer, it built you up nicely, but then when you came off it… wow.

You're spending all your money in your account on drugs. You start borrowing from family, telling them you'll pay them back next week. Well, that was a lie. I was hiding.

People would come up to my door, I wouldn't want to answer to friends or anyone. I was embarrassed, ashamed, and I was depressed. Things are going through my mind: "Why didn't I get insurance? Why did I leave Chelsea?"

I wanted help, but I didn't want to admit it.

Internally, I was crying for help. I wanted the police to arrest me, but they wouldn't, because I was still denying it and hiding it. I was working for a company, delivering tools and whatnot. I got in early in the morning, I was stealing radiators, stealing lead rolls to sell. I was desperate to get caught. I wanted help, not by telling people, but by people catching me. I'd have said: "This is what is happening to me…"

I was DJing around that time. There were three of us, spinning soul and reggae. Long parties, and this was my income for the drugs.

I started taking crack in 1990, and in 1996 I was diagnosed with my first of two cancers. I took it very lightly.

I had the chemo. They told me it would kill my immune system, I could get a cold and it would take me right out. I thought: "Yeah alright, cool, whatever." I went home with my partner, I had a cold, and kept drinking honey and lemon, what my mum used to give me. For two weeks I was sipping honey and lemon, but the cold wasn't going.

I woke up one morning and was paralysed. All I could do was move my neck. I turned to my partner, told her, and she said: "Shut up Paul, stop being funny," because I was a joker at the time. She's tried to move me, and my arms and legs have just flopped. I should have gone into the doctors earlier, but it was able to spread across my whole body.

The ambulance got me in Stoke Newington, and they kept telling me to stay awake. I nearly died, just as I got to the hospital.

I recovered, but I was on a rapid downward descent into darkness. My heart was then torn beyond repair when my 10-day-old son died, having been born with a heart defect, while being held in my arms. Nothing could numb the pain or trauma of what I was feeling. Disaster after disaster after disaster - how can anyone go on after this?

_____

Then came Simon.

Simon Chandler was an apprentice at Chelsea. I was at my lowest ebb, walking down the road looking for drugs. I saw this figure, recognised it was Simon, but couldn't find anywhere to turn away. I pretended I didn't know him, but he'd heard what I was going through. He said: "Do you know what you represent? We need to sort this out." He put me into rehab and he got me back into the gym. He took a lot of s**t from me. He talked to me like I was a kid sometimes, and I'd react: "Who do you think you're talking to?" and he'd reply: "I'm talking to you, Canners." It's what I needed.

The rehab programme came with counselling. I thought: "Counselling? Opening up to strangers? Nah, no thanks, f**k that."

So, in my first session…

"How are you?"

"Yeah fine."

"Why are you here then?"

"That's a f*****g silly question isn't it? I'm in rehab, what do you think? You tell me."

"No, you tell me. What do you want to do?"

"What do I want to do?! These are silly questions."

This was pointless. I wanted to get up and go, and he said: "This is part of the programme, if you leave you'll be chucked out."

So I thought, f**k it, I'll sit down for an hour then. In silence.

So they tried somebody else, and I still gave him hell.

"Do you think the problems you're having are to do with your mother?"

"How f*****g dare you? You don't know my mother!" I saw it as an insult.

"How about your kids?"

"How f*****g dare you? What do you know about my kids?"

It went quiet.

Bam.

He'd already hit the nail on the head.

I was constantly thinking about my mum and about my kids. It was about them, and I started to release, open up, and I didn't want that first session to end. I wanted to release so much.

I'd been told not to open up, but here I was, opening up, and it helped me. Every time it got near to my next session I was looking forward to it. More and more came out of me about my mum. She was disciplined, I couldn't open up to her. As much as I wanted to, she couldn't show that love. It was the main thing for me.

Everything started to fall into place after that. It was incredible.

At this time I'd had eight different children with eight different women, and when there was an argument I'd just get up and run. I wouldn't want to get involved in emotions.

To realise this, it took a counsellor. It helped so much, that my shoulders began feeling lighter. I felt so, so good about it.

I had relapses. But on those occasions, I knew I had an issue, and helped myself, went straight back to rehab and sorted myself out.

_____

It's about resilience. I've been knocked down so many times, cancer, death, racism, depression… and I'm able to share my history with those in trouble.

I'd been talking in schools, then I applied to become a teaching assistant. At first, I thought: "I never went to school, how am I going to get a job?" I'd never been to an interview in my life. I was nervous as hell.

They showed me around the school and said: "When can you start?" I cried. I phoned my mum, and she was actually proud. She was more proud of me being a TA than a footballer. The boy who bunked off 75 days off in a term was now working at a school!

Nowadays I'm more positive. The Paul Canoville Foundation helps me as well as others. It's about mentoring, having someone to talk to, because a lot of kids are like me, without a father figure. That's where I come in, and tell them: "I know how you're feeling."

We help kids who may not have got the career they wanted to, but we help them focus on something they can give back to the community, particularly coaching badges. We're a sporting foundation, but we look at mental issues, knife crime, everything. I just want to give back.

Whether man or woman, and you feel it's difficult to share and let people know what's going on, don't think like that. There are so many people out there going down the same road. Talk to someone. Depression is a disease, but it can be looked after if you ask for help. Share it.

_____

Paul Canoville spoke with Sky Sports' Gerard Brand

If you are affected by these issues or want to talk, please contact the Samaritans on the free helpline 116 123, or visit the website.