How Liverpool became a city and a team reborn

Watch Man City vs Liverpool live on Sky Sports Main Event and Sky Sports Premier League from 8pm on Thursday July 2; Kick-off 8.15pm

Thursday 25 June 2020 18:40, UK

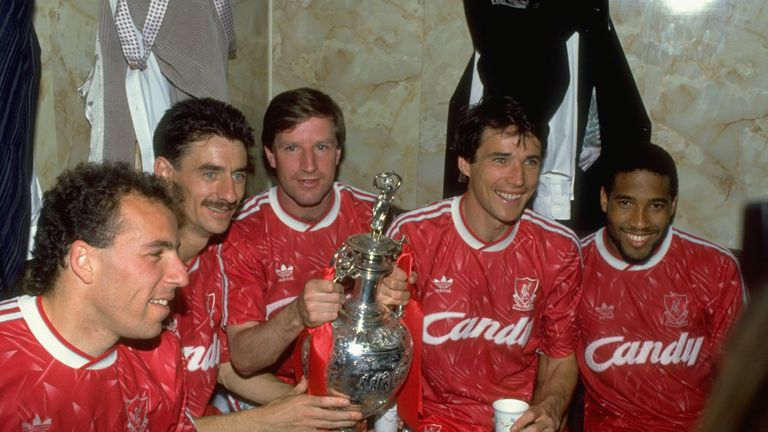

"The most important title is the most recent one. You can tell by the reaction of everyone here that they enjoy winning." Kenny Dalglish, May 1, 1990.

- How can Liverpool win the title on Thursday?

- Premier League restart: The live games on Sky Sports

- NOW TV Sky Sports Month Pass for £25 a month

It was Liverpool's 18th league title. The 1989/90 season brought the club's most successful decade to a close, but it was also the darkest economic period for the city. Over the next three decades, a physical and economic regeneration took place as the club fell from its previous heights. Now, it is back at the top once more.

Ian Salmon, who wrote Those Two Weeks, a play depicting Liverpool life immediately before the 1989 Hillsborough disaster, paints a picture of 1990 as a time of reinvention. "You've had that 1980s Boys From The Black Stuff moment where, as a city, we were really low but defiant," he explains. "Even though nobody had any money we did have a great time because you were seeing the best bands and watching fantastic football every week."

The Conservative government came close to abandoning the city in the aftermath of the 1981 Toxteth riots, raising the prospect of its partial evacuation. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Geoffrey Howe, told Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher that the city was "much the hardest nut to crack".

In a confidential note in the immediate aftermath of the riots, only made public in 2011, Howe said that plans for an injection of public spending had to be rejected. "Isn't this pumping water uphill?" he asked. "Should we go rather for 'managed decline'? This is not a term for use, even privately. It is much too negative, when it must imply a sustained effort to absorb Liverpool manpower elsewhere."

As Liverpool's unemployment nudged above 20 per cent in the mid-1980s, the music scene thrived with Echo and the Bunnymen, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, The Icicle Works, The La's and The Farm providing a soundtrack to the city's two great football clubs.

"There was an economic hardship and mass unemployment, but Liverpool was a hugely creative place," adds Paul Gallagher, Museum of Liverpool deputy director. "Speak to people involved with that and they look back with great fondness at the creative output of the city, and the football teams were a part of that."

"Coming out of the 80s, Liverpool had its problems, but when people talk about the dark days of the 1980s there was a real vibrancy about the music and football scene," adds Peter Hooton, lead singer of The Farm. "A lot of people did move out, there's no doubt about that. Scousers went all over the world, lots just went to London. People moved because they had to, economically. That's what certain songs were about then, people leaving the city.

"It was a very political city, even as an eight-year-old in 1990 I was aware of that," says The Anfield Wrap's John Gibbons. "We used to play a game at school with a song that wasn't very complimentary about Maggie Thatcher, and we all knew about the poll tax. That's mad when you think about it. I don't think there's any eight-year-olds singing about Boris Johnson today."

"Going into the 90s, Thatcher is still in power, but you've got the revolution of acid house, with Liverpool following on from London and Manchester in terms of the dance scene," Salmon adds. "Students were attracted by the music and it becomes a nightlife city. You had clubs like The State and Quadrant Park, people are coming in for the dance scene. Liverpool is becoming a much fresher place, a new dawn starting."

The football team and the city travel in different directions for the next 10 years. "You get to Italia 90 and you see the beginning of the gentrification of football because suddenly the media realises what football means to the viewing public," Salmon continues. "Football becomes a commodity that can be sold. Manchester United capitalise on that and we don't. Even though there are a couple of FA Cups and a League Cup, we stand still for the rest of the decade."

"With the advent of the Premier League and the riches that came, Liverpool didn't know how to deal with that," Hooton agrees. "Liverpool in the mid-90s were playing some magnificent stuff, but they didn't have the steel and the mentality of Manchester United at that time, which I think Eric Cantona brought to them."

As the team lost ground on United, the city was beginning to thrive. "The effect of Cream nightclub on Liverpool is underestimated," Hooton continues. "People started coming from all around the country as rave tourists. That's when Liverpool got its reputation not as an economically depressed city, but as a party city. You've got to hold your hands up to the lads who started Cream because the insight and vision they had was absolutely brilliant.

"Cream makes such a difference to the way the 90s goes for Liverpool because it gives it a new identity," Salmon says. "Even the bands that were huge in the 80s are starting to drop off a bit, so Cream comes in as one of the first super clubs.

"By the late 90s people started to see Liverpool differently, as a city you could come and visit safely. And the tourism industry started to develop," adds Hooton.

The political struggles still bubbled on the surface. The dockers dispute over workers' rights and pay that began in late 1995 and lasted until January 1998 drew the support of Liverpool stars Robbie Fowler and Steve McManaman. Both players donated to the dockers' fund and wore t-shirts in support of the workers underneath their shirts during a European Cup Winners' Cup tie against SK Brann in 1997, with Fowler being fined for revealing his after scoring.

"To see two local lads, with more money than ever before coming into the game, but who aren't dissociated from supporting the people of the city, that was a fantastic moment," says Salmon.

1998 marked the end of the famous Anfield bootroom when Roy Evans parted company with Gerard Houllier, leaving the Frenchman to take sole charge of the club. Houllier embarked on a five-year plan to build a team fit for the 21st century. In the summer of 1999 McManaman, Jason McAteer, Rob Jones, David James, Paul Ince and Steve Harkness were replaced with Sami Hyppia, Didi Hamann, Sander Westerveld, Djimi Traore, Vladimir Smicer and Titi Camara. It was the most significant overhaul of playing staff in a single summer that the club had ever seen. A famous cup treble in 2001 followed. But by the end of Houllier's stay in 2004, Liverpool appeared no nearer another title.

The city also embarked on existential change. In 1999 Liverpool City Council passed a resolution for the redevelopment of the Paradise Street area of the centre. A year later the Duke of Westminster's Grosvenor Group was announced as the developer and the project was extended across a much larger site. In 2003 Liverpool was awarded the European Capital of Culture City for 2008, with the construction of the Grosvenor development beginning in 2004.

"When they won the European Capital of Culture bid in 2003 I remember a commentator saying, 'Great, Liverpool has five years to find some culture'," says Gallagher. "It was a really negative comment and Liverpool had been battling that negative stereotype for a long time, decades really. But there is a defiance here and we got on with it. Two thousand and eight turned into one of the most successful Capital of Cultures ever. It was a real thrill for us to say to visitors, 'This is our city, this is what we have got to offer'."

"I remember a period in the early 2000s when every building in Liverpool that was any good felt like it was 300 years old," says Gibbons. "We had great architecture here, but nothing had been built for a hundred years. Other northern cities had modernised, with the big skyscrapers. Where's ours? That's why the Capital of Culture was so exciting, it felt like finally there were exciting things happening rather than hard-luck stories. That's when you began to see Liverpool as a modern city."

The completed Liverpool One development comprised of over 200 shops, more than 500 apartments, three hotels, 25 restaurants, a cinema and a five-acre public park. But its biggest achievement was the physical way it opened up the city's attractions elsewhere.

"The one great thing Liverpool One did was join the tourist areas of the Albert Dock and Pier Head to the shopping areas," says Hooton. "That's been a massive benefit to the city. If you look at the tourist figures since the Capital of Culture in 2008, they have absolutely rocketed."

A decade after the European Capital of Culture, Liverpool City Region's visitor economy was valued at over £4.9 billion. In 2018 it welcomed 67.3m visitors to the region and supported over 57,000 jobs.

"That's not just down to the Beatles and museums, it's down to football as well," Hooton continues. "A lot of people turn their noses up at football tourism, but I remember back in the 70s having a Liverpool scarf with 'Supporters all over the world' written on it, we wanted to be a world-famous club. We looked with envy at Real Madrid and Barcelona, but now Liverpool are up there."

It was Rafael Benitez who put Liverpool back on the world map in his first full season in charge, bringing the Champions League trophy to Anfield in 2005. "Gerard Houllier gave us back a pride and discipline in the team, but Istanbul was pivotal," Hooton adds. "The way they did it was a fairy tale. That increased Liverpool's fan base around the world and it bought Rafa Benitez a bit of time."

When David Moores ended his 16-year ownership of his local club in 2007 and sold to Americans Tom Hicks and George Gillett another chapter would begin.

"The days of a local guy done good were gone and you needed to look not just at millionaires, but billionaires to push you on," says Gibbons. "That was a big deal for Liverpool to take that on, so for it to unravel so quickly was frustrating. Up to that point, we'd supported our team on a Saturday and worried about who we were going to sign. Suddenly we had to become experts in finance, brokered buyouts, leveraged buyouts. It's all the things you shouldn't have to worry about as a football fan."

Benitez's Liverpool finished second in 2008/09, but the manager became embroiled in a dispute with the owners over the direction of the club. In 2008, The Spirit of Shankly was formed after a huge meeting of Liverpool fans in The Sandon pub next to Anfield. It aimed to hold Hicks and Gillett to account as mounting debts caused huge concern among supporters.

"Nobody expected fan resistance, it had never happened before," Hooton explains. "We had some well-placed journalists getting information that helped us with the movement. I think it was a crucial period because you can't find anyone who didn't support the campaign. I remember the most we had was 5000 fans on marches, after the games, and that was a tenth of the fans in the ground.

"When FSG [Fenway Sports Group] took over and met with Spirit of Shankly, the one thing they said was that if it hadn't been for groups like that they wouldn't be in control. It was an incredibly successful protest, a modern-day digital age warfare. I remember somebody texting me from the Premier League saying their website had crashed because of all the emails and messages from Liverpool fans [protesting about Hicks and Gillett]. I asked what we were supposed to do about it and he replied, 'Can't you call them off!?' Things like that were instrumental in changing attitudes."

The ousting of Hicks and Gillett in 2010 came at a price. Benitez had gone by then and the subsequent Roy Hodgson era is not remembered fondly. It has taken FSG a decade at the helm to bring Liverpool to the point of that elusive 19th title.

"FSG haven't been perfect by any means," says the Liverpool Echo's Ian Doyle. "It was only four years ago that they wanted to put season ticket prices up to £77 per match. About 10,000 fans - and we're talking hardcore fans who had been going to the game for years - got up and walked out of the match. It's been a long haul for them, they've changed the manager a couple of times, they've changed the ethos of the club, they've changed the way Anfield looks. They're going into a new training facility in Kirkby. They've pumped in hundreds of millions of pounds in infrastructure, the same with the team, and it's all on the basis of Liverpool becoming this winning machine which is what they have become in the last 18 months under Jurgen Klopp.

"In 1990 they had been out of Europe for five years, you didn't have the big European names. Liverpool were coming to the end of the cycle of their success, so it was like a last hurrah for that particular team. It has ended up that Liverpool have had to arguably produce the best team in the entire history of the club to win back the title."

"The globalisation of football has changed everything since their last title," Gallagher adds. "Liverpool's support was pretty much based in the city, you'd have a few exiled Scousers who had left the city coming home for the match. Now you can feel a Liverpool home game around the city because of the international fan base that brings huge economic benefits. The last two years Liverpool have got to the Champions' League final, and the city was an incredible place to be. People were coming here just to watch the match in pubs and bars. That would never have happened 30 years ago."

A parallel story, totally intertwined with the fortunes of the club and the city has been the fight for justice after Hillsborough.

"It will always be in Liverpool fans' DNA, it's been such a struggle over the years," says Hooton. "The truth is out there, but a lot of people feel justice hasn't really been done. But everything that shaped us during and immediately after that period is in the mindset of Liverpool fans. It'll be an emotional moment when Liverpool do win the league. I don't think people appreciated at the time that the club was decimated by Hillsborough. Even though they carried on playing games I don't think they ever recovered from the shock and trauma. That's why Liverpool fans always look back to that period as very significant in terms of what happened to the city and the football club."

"It's still open and always will be open," Salmon adds. "The judicial inquest showing that fans weren't to blame wasn't closure as such. We expected a prosecution to follow, but the only one that came about was a fine. 96 people died and there was a small fine for health and safety issues. That's never going to satisfy anyone. If we had won the league last year it would have been for the 96, when we win it this year it will be for them. It's why we have the 96 on the back of the shirt. Every bit of success we have has the people we lost at Hillsborough within it."

Under normal times the city centre would become the focal point for tens of thousands of Liverpool fans when the moment to celebrate the 19th title arrives. The coronavirus pandemic has put an end to that. Like every other city, there is an uncertainty about the future. But the last 30 years have seen Liverpool transformed beyond anyone's imagination back in 1990.

"Back then you'd walk through Liverpool and think this is a Victorian city going through hard times," says Hooton. "The very fact people have invested in the place means there is a confidence in the city."

"I think we are continually growing," suggests Salmon. "But there are some things that have been put into place that haven't worked. We've got a hospital that desperately needs replacing and a half-finished one next to it that was done by Carillion that doesn't look like it will ever be finished. I'm from Bootle, we've got this massive container dock on the front at Seaforth with huge new cranes, but Bootle itself is still struggling and needs investment. When Everton go down to Bramley Moore it will open up the whole dock area, where some buildings have been neglected since the 1980s. There's still space for huge amounts of investment in Liverpool, we are far from the finished article."

"The challenge of any city is to offer its people the opportunity to stay," says Gallagher. "In the 80s Liverpool saw its population halve because those opportunities didn't exist. I think the way Liverpool thinks now is different. It is a place that is confident, it recognises the value of culture and creativity. The Baltic Triangle, the development of the whole docks system, these are physical examples of the cultural regeneration. Having an arena has brought a whole new range of artists and people to the city. Although we are in a similar position now with austerity, there are cuts having a negative effect. One can't underestimate how much that still sits underneath, but my hopes for the city are positive."

The physical changes to the city are all around, but the psyche of Liverpool has changed just as dramatically. It has become a place of growth and possibilities, where ambition can be fulfilled.

If Manchester City fail to beat Chelsea on Thursday, then Sky Sports will be on air with a Liverpool title winners special show on Sky Sports Main Event and Sky Sports News from 10pm