What gave Xavi Hernandez and Andrea Pirlo an edge on the rest? The secret to his vision

Friday 10 November 2017 16:42, UK

What made players such as Andrea Pirlo, Xavi and Frank Lampard so good? In an extract from his new book Edge: What Business Can Learn From Football, Ben Lyttleton details the secrets of their success...

Dr Geir Jordet is a Norwegian professor of psychology who played football for lower-league side Strommen IF. He wrote his Master's thesis and PhD on the role of vision, perception and anticipation in elite-level performance: in short, the areas of performance where psychology can directly affect the outcome on the pitch. He has analysed Ajax players, shared his findings with the Ajax staff and works as a consultant to Cruyff Football. He will teach me about the art of decision-making.

He breaks down the key factors of decision-making in football into three segments. These also work away from the pitch. The first is visual perception, which he describes as the ability to take in and interpret information; the second is visual exploratory behaviour, or the ability to actively search and scan to collect information; the third is anticipation, or the ability to see what is about to happen.

Jordet started out his research by taking a camera to matches and filming one player for the full 90 minutes. A bit like the art-house Zinedine Zidane film Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, but starring Jordan Henderson instead. Jordet filmed about 250 players with close-up images, and realised that they all did different things before they received the ball.

He showed me a video of Andres Iniesta in the 2010 World Cup final. In the 10 seconds before he scores the winning goal, you can see Iniesta in the middle of the pitch, scanning for information. He is making sure his eyes are exposed to the most relevant information on the pitch. That is his starting-point: before his cognitive processes kick in, before he makes a decision, before he uses signal detection and memory, he makes sure that the relevant information has hit his retina.

Frank Lampard was the same. Better, in fact. Jordet has a 16-second clip of Lampard that has become a YouTube favourite. Filmed in October 2009 during a Chelsea game against Blackburn, Lampard is in the opposition half. He looks over one shoulder, then the other. He jogs into space, and looks over both shoulders again. He is capturing information for when he has the ball. He looks around 10 times in seven seconds before he gets the ball, looks up, jinks past one man (whom he saw coming) and plays a team-mate into space.

Lampard had the highest 'Visual Exploratory Frequency' in the Premier League during the period of Jordet's research. He counted exploratory behaviour as: 'A body and/or head movement in which the player's face is actively and temporarily directed away from the ball, with the intention of looking for information that is relevant to perform a subsequent action with the ball'.

The study looked into the search frequency of 64 players over 118 games, covering 1,279 game situations. Lampard averaged 0.62 searches per second before receiving the ball. Steven Gerrard was very close on 0.61. Jordet believed that players who actively scanned their surroundings before they received the ball would produce a higher percentage of successful passes once they received possession. Was he right?

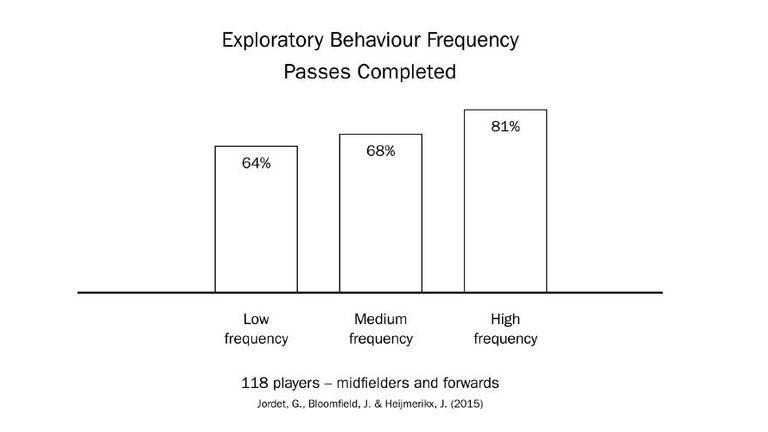

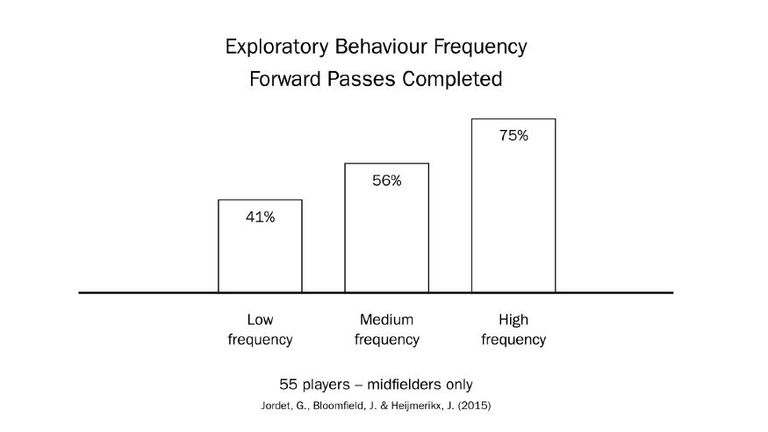

Jordet divided the data into three sections: those who looked the least, those who looked the most, and those in between. The pass completion for those who looked the least was 64 per cent; for the middle group 68 per cent; and for those who looked the most, 81 per cent. This was an important finding but not yet proof that looking around more leads to enhanced performance. After all, maybe the 81 per cent of passes were all safe passes to the side or back to where the ball came from. He changed the variable so the data only looked at forward passes completed. The sample set was smaller, down to 55 players, but the result was more powerful. The highest-exploring third hit nearly twice as many forward passes, 75 per cent success rate, as those players who did not explore as much, 41 per cent.

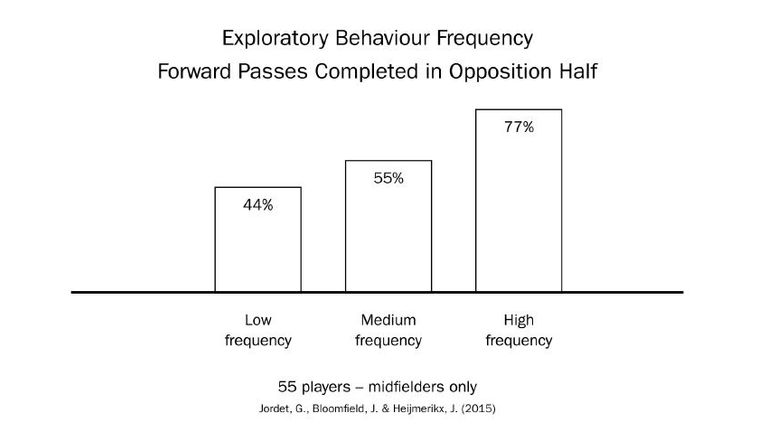

He tweaked the variable one more time and looked at forward passes completed in the opposition half. Again, the same results. The finding that there is a close relationship between exploratory behaviour and performance did not surprise Jordet.

Increased Visual Efficiency Behaviour (VEB) leads to more information, which allows athletes to improve the ability to effectively process this information. Jordet calls it Prospective Control. It's an ability to see what is about to happen, though it's only meaningful in practice if it can be linked to action. Things change fast and what's relevant now might not be relevant in three months; or if you're Lampard, in three seconds. Collecting information, updating the overview of your terrain; that allows you to act before others.

Jordet later had the chance to ask Lampard about his search frequency. They were both on stage at a conference when Jordet spoke about his findings. Also present was Tony Carr, who had been in charge of the West Ham academy when Lampard was coming through the ranks. The moderator asked Lampard why his search frequencies were so high. "I don't know where it came from, maybe I was born with it," he said. "Anyway, it's logical that you scan around because you need to know what's around you."

This is the problem with asking elite performers how they became so good at something. A lot of the time they say it's natural, or they have no idea. That's no help to people like Jordet, who are trying to learn about the process. Which is why he was so grateful for the intervention from Carr, who had been listening quietly, but then interrupted.

"In the first game Frank played for West Ham, his dad [Frank Lampard Senior] would sit in the stands and shout at his son all the time," said Carr. "He'd say the same thing every time: 'Pictures! Pictures!' He just wanted Frank to have a picture in his head before he got the ball. That was all. 'Pictures!' Lampard sat up. "That's true, he was yelling at me and I did what he said."

Jordet finally had his answer. Lampard had not been born with it; nor is it particularly logical. Lampard was encouraged to 'take pictures' from a very young age and never learned any differently.

Pictures are what Jordet has been teaching to the kids at Ajax. He shows them two videos. One is of Andrea Pirlo playing for Juventus against Torino in 2012. He is in his final season at Juventus, has grown a thick beard and, aged 35, is even slower than at his peak. But still he looks around before he gets the ball; not quite so prominently as Lampard, but there it is, the look here, the glance there. And then, when he gets the ball, the screen freezes. At the point the ball touches his foot, where is Pirlo looking? Somewhere else entirely. Not his foot. He is already looking for the answer, the next move, the danger pass. He knows the ball is coming, and so he can look somewhere else.

The second video is of players training at a Bundesliga club. There are six players in a square, and three balls. The players pass to each other, and it is simple stuff. Ten metres apart, pass, control, pass, control, pass, control. They do 60 or 70 repetitions of this. The control is perfect, the passes are accurate. But every time they receive the ball, every player looks down at his feet. Pirlo doesn't do that; nor do most other players.

"What they are practising is one of the most common training skills of all, but it rarely happens in the game," Jordet says. Who has time to look at the ball once it's at their feet? "They are developing a skill that they do not need. Almost every single player in football, even the ones at the highest level, have hundreds of repetitions of this skill every day, when they warm up and pass the ball back and forth, one to the other. Learning to control the ball without looking at it - now that would be useful. After all, learning something new isn't that complicated. What's hard is to forget something that you have already learned. To de-learn it."

Ajax takes their players' VEB seriously. When they played a UEFA Youth League quarter-final against Chelsea in May 2016, their starting eleven all had the highest VEBs in their positions in the entire youth academy. Jordet said that anything over 0.50 visual searches per second is very high. I sneaked a look at a table of selected players he has filmed at the highest level and saw that Lionel Messi was above that. Others around him included Zlatan Ibrahimovic, Luka Modric and Pirlo. Cristiano Ronaldo was lower than the others - but there was a reason for that. He times his scans differently, only looking immediately after every touch of the ball from a team-mate. As he sees where the ball is heading, he knows that he has half a second where he doesn't have to look at the ball, and can look around.

One player was so far above the rest it was scary. Xavi Hernandez scored 0.83 in the table. Whenever he received the ball and had not scanned and sampled the information, he played the ball back from where it came. He took no risk when he didn't have the information.

"Think quickly, look for spaces. That's what I do: look for spaces. All day," Xavi told the Guardian in 2011. "I'm always looking. All day, all day. [He starts gesturing as if he is looking around, swinging his head.] Here? No. There? No. People who haven't played don't always realise how hard that is. Space, space, space. It's like being on the PlayStation. I think ****, the defender's here, play it there. I see the space and pass. That's what I do."

And was he born with it? No, he learned it at Barcelona, in the system that Cruyff instigated. 'Some youth academies worry about winning, we worry about education,' he said. 'You see a kid who lifts his head up, who plays the pass first time, pum, and you think, "Yep, he'll do." Bring him in, coach him. Our model was imposed by Cruyff; it's an Ajax model. It's all about rondos [piggy in the middle]. Rondo, rondo, rondo. Every. Single. Day. It's the best exercise there is. You learn responsibility and not to lose the ball.'

What I realised is that brilliant players don't play a pass without seeing it; the brilliant players look so early that they play the pass before we have even seen that they have seen it's a pass. And it is not about having the best eyesight, but about how you assess the information. As Jordet put it: "I would have more faith in Xavi's abilities as a CEO than someone whose scores are very low on this."

Options, options, options. Therese Huston, Faculty Development Consultant at the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Seattle University and author of How Women Decide, advises to always give ourselves three options. Huston gives the example of a company that is thinking about building a parking garage. "Instead of just should we build a parking garage or not, three options would be: should we build a parking garage, should we give all employees bus passes, or should we give our employees the option to work from home one day a week?"

Once you generate more options, you can take a better decision. Xavi never has two options. He sees things so quickly, and clearly, that he always has at least three, and probably more, to choose from. It's why he makes such good decisions.

Edge: What Business Can Learn From Football, by Ben Lyttleton, is available to buy now.