Ouissem Belgacem

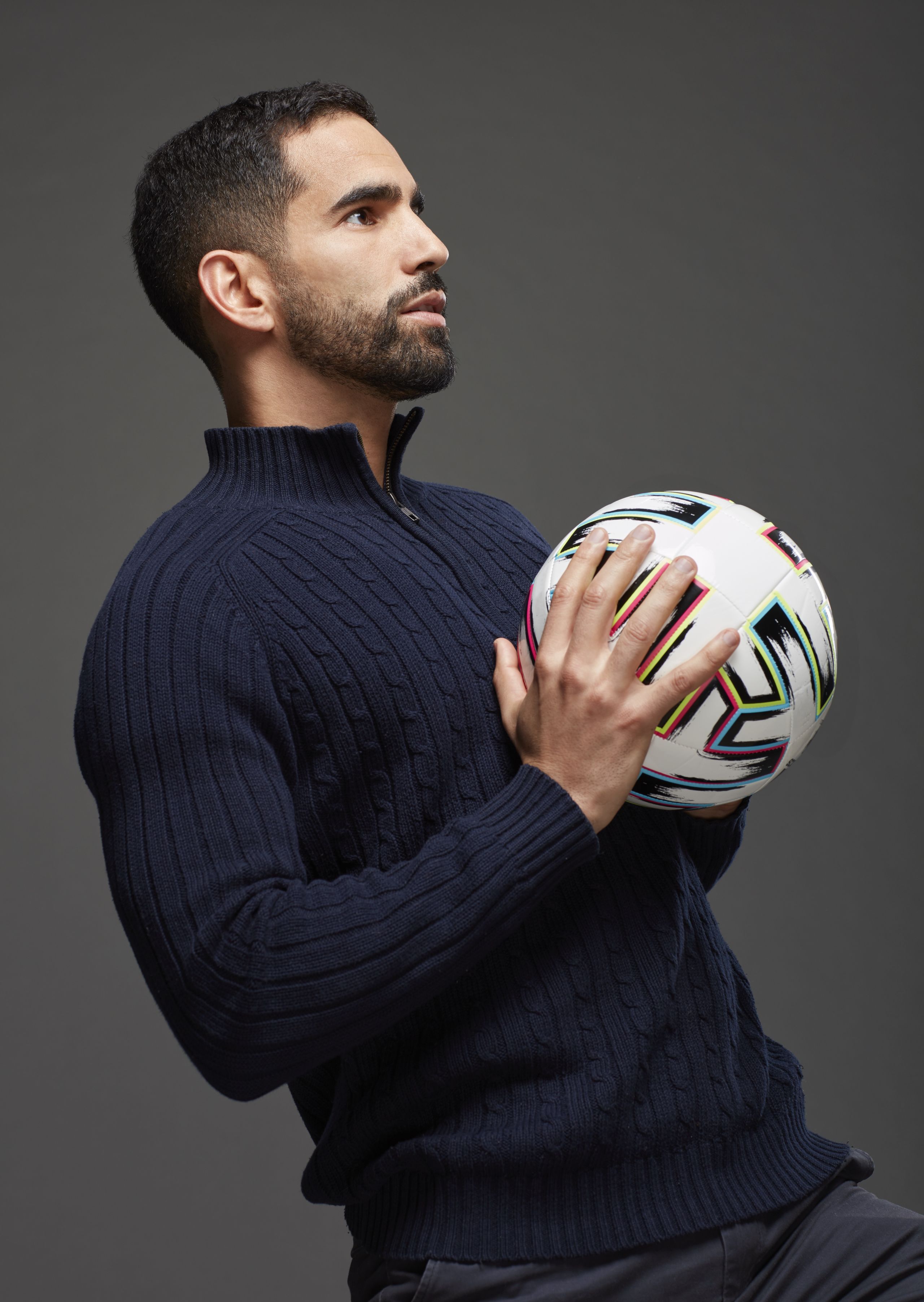

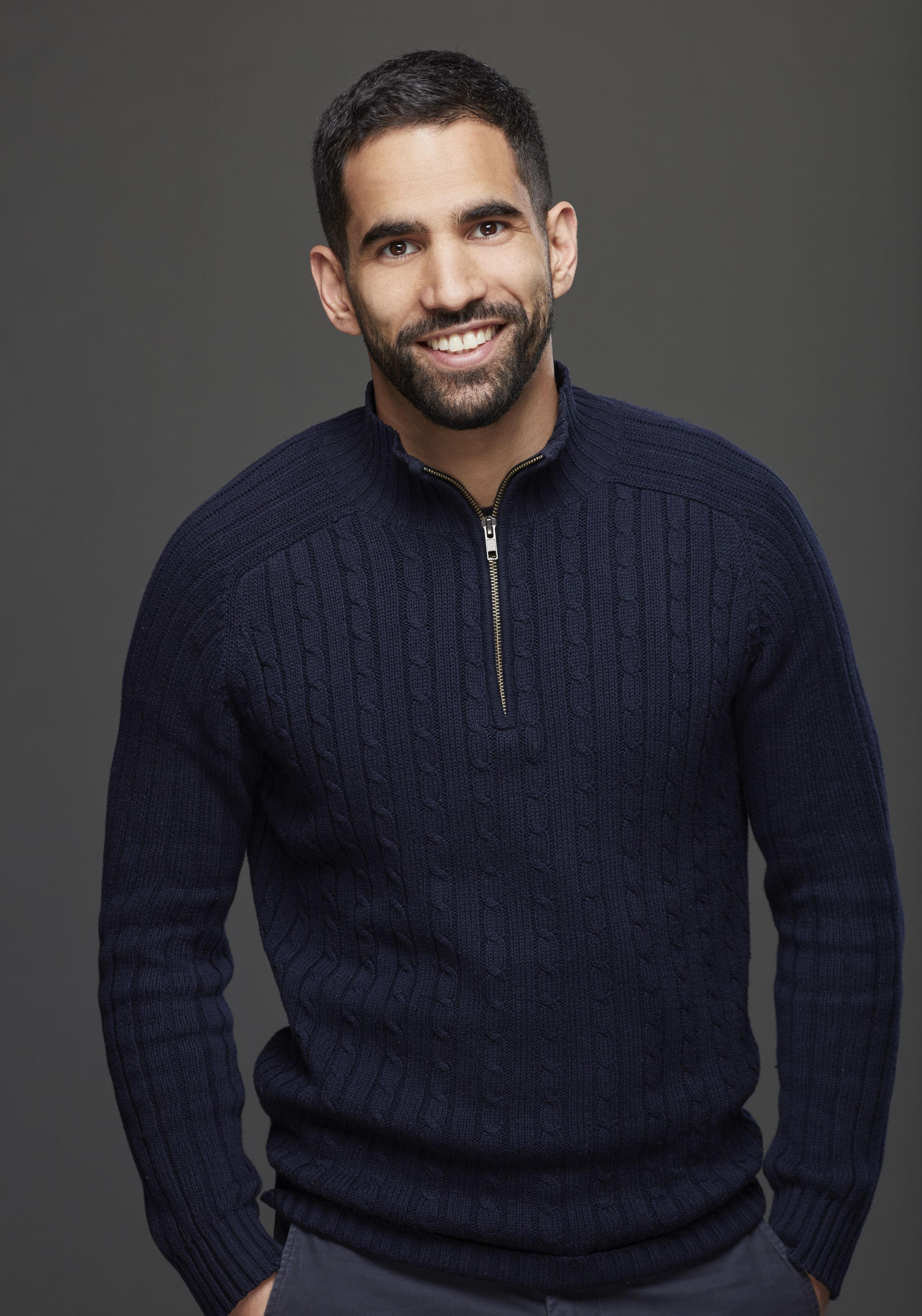

The man who shocked French football

L'Equipe, Le Monde, Liberation, GQ France… in recent weeks, former footballer Ouissem Belgacem has been seen and heard across French media's biggest publications.

There have been primetime TV interviews and radio appearances too, and the requests keep coming. France is fascinated by what he has to say.

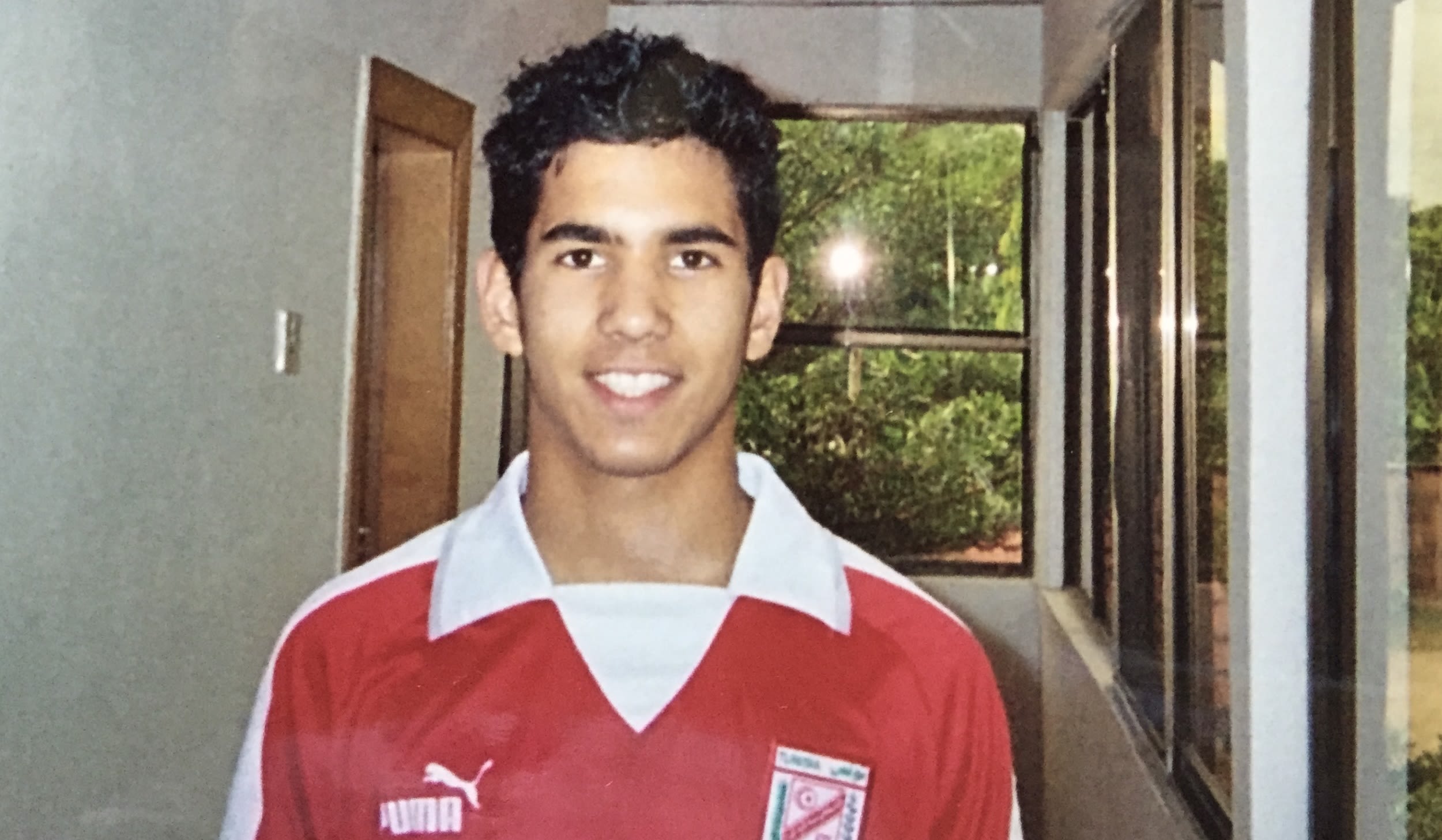

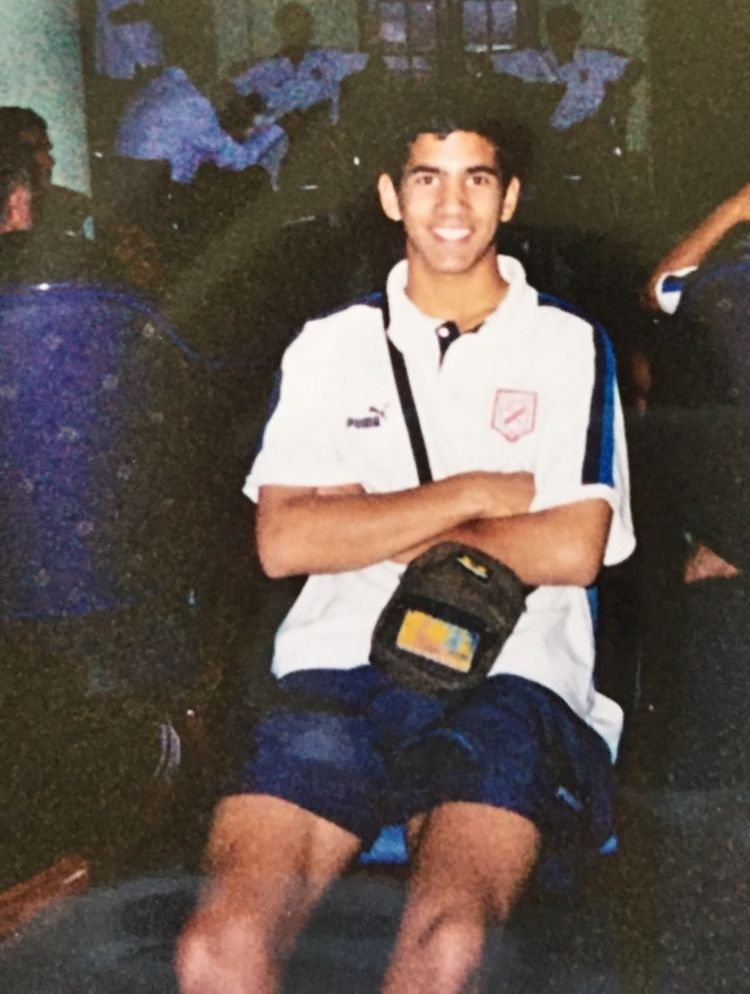

The scale of this visibility would have terrified Belgacem as a young man, when he looked set to break through at Toulouse's prestigious academy.

An athletic, gifted defender, he also represented Tunisia, his parents' homeland. The world was at his feet - yet he would rather the earth swallow him up than have to share his secret with anyone other than a shrink, let alone the entire nation.

"For a long time, I hated myself for being this anomaly - a footballer who was gay"

"All the energy I've put into changing sexuality... if only I could have put that into football"

- Ouissem Belgacem

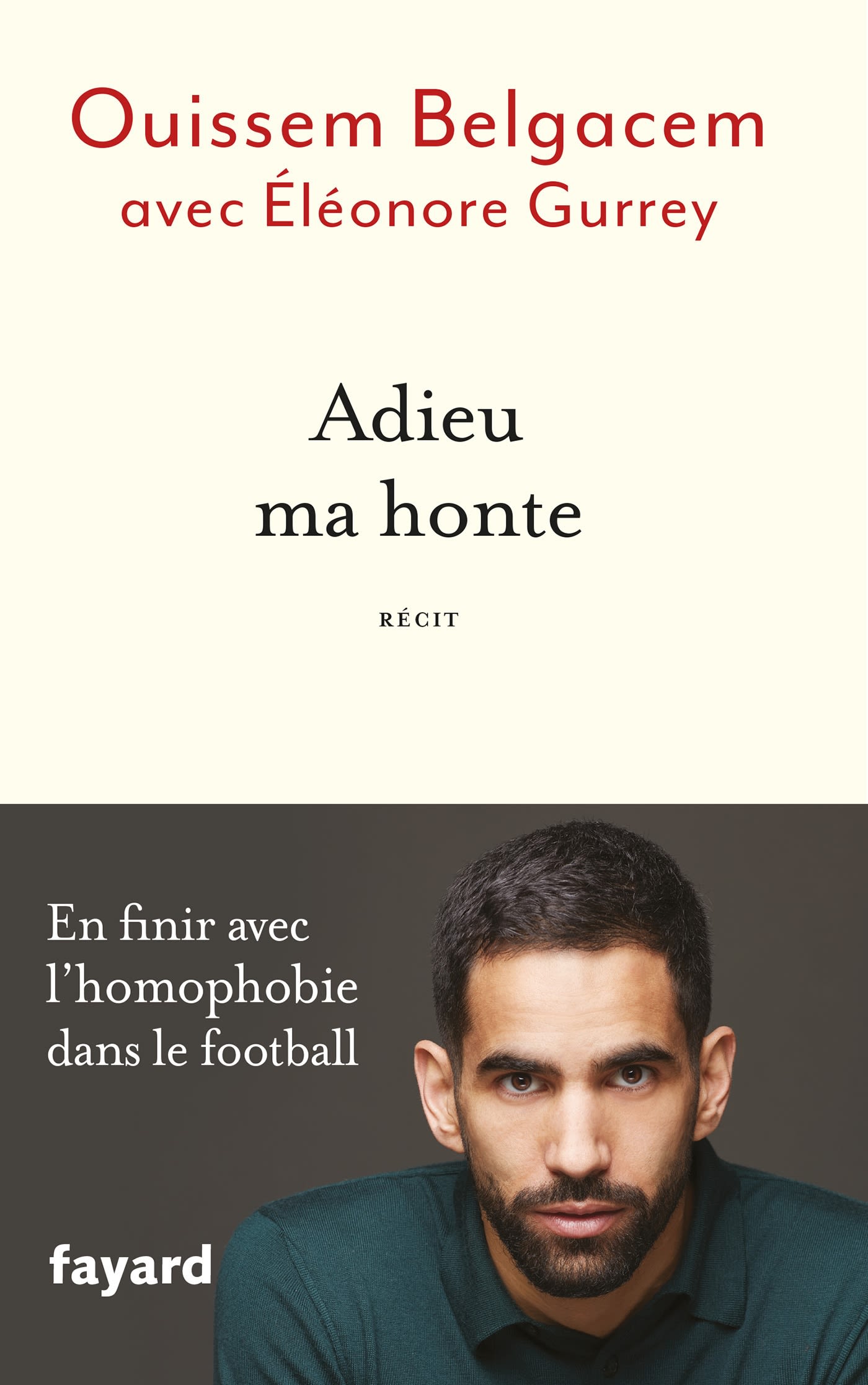

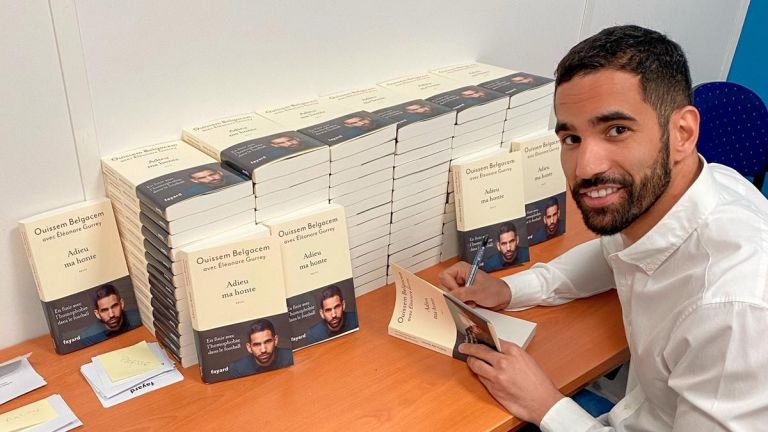

Belgacem has written a book - a startling, soul-baring memoir titled 'Farewell To Shame' - through which he banishes all his previous feelings of embarrassment and inadequacy.

Its publication has launched him into the limelight in France, solidified his own sense of pride, and advanced discussions across the country on identity, mental health, and discrimination in football.

Yet what makes Belgacem's story even more extraordinary for the game is that it transcends his nationality. Lessons learned from his experience would be applicable to academy set-ups anywhere.

He played in the US, where he faced appalling Islamophobia; he laboured to carve out a new career in London, where he discovered community and self-confidence; and with the support of former team-mates such as Tottenham's Moussa Sissoko, he created a ground-breaking business called OnTrack Sport that helps athletes acquire the skills they need after the bubbles of their professional contracts burst.

Revelatory and rare, the autobiography also offers hope that homophobia's silent stranglehold on football can be weakened if those with power and influence step up to help. "I might lose clients because of writing this book," Belgacem tells Sky Sports, speaking from his apartment in Paris.

"But I wrote it to be like a mirror - I want the football industry to look at itself and realise what is wrong in the system.

"I dream of a world where all kids, all teenagers, can fight equally to try to become professional. Today, this is not the case."

Belgacem describes how he struggled with internalised homophobia while growing up in the challenging environment of Toulouse's academy

Belgacem decribes how he struggled with internalised homophobia while growing up in the challenging environment of Toulouse's academy

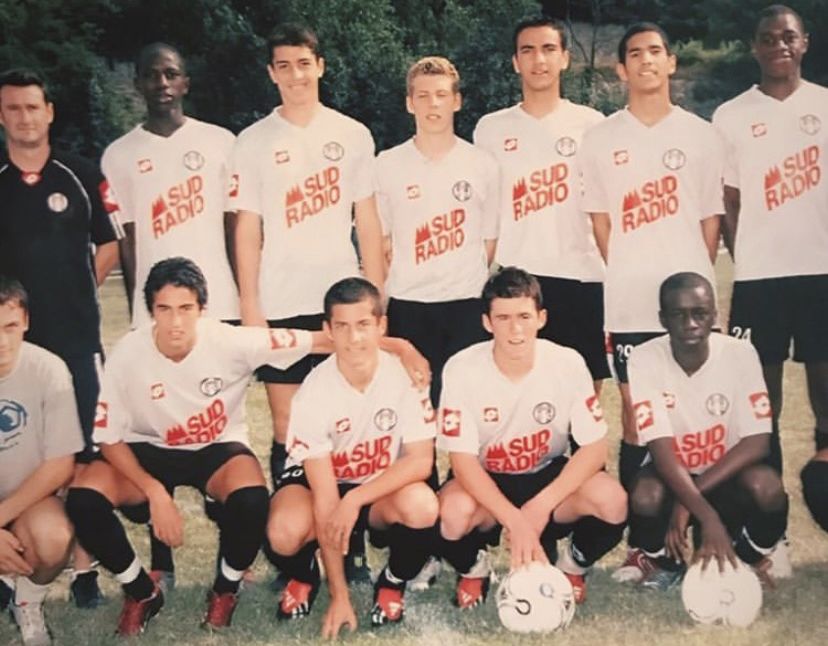

He joined Toulouse at the age of 14 and spent six years in their academy. His first roommate was Kevin Constant, formerly of AC Milan, while Sissoko and Senegal international Cheikh M'Bengue remain among his closest friends.

Belgacem was a classy centre-back, tough and tactically adept, modelling his game on that of John Terry. His talent was spotted by the Tunisian FA (he featured in African U17 Championship qualifying) and in 2006, he was a cornerstone in the Toulouse team that finished as runners-up in the national youth league. They would have been champions were it not for the individual brilliance of Miralem Pjanic - then of Metz, now of Barcelona - on the day of the final.

Etienne Capoue joined the age group in 2006 and would go on to play for France alongside Sissoko. But Belgacem did not break through - he didn't even turn professional. While his peers prospered and progressed, he suffered the energy-sapping effects of internalised homophobia in an environment that constantly reinforced negative stereotypes about gay people. He fought in vain to flip his own sexuality to straight in a desperate bid for validation.

"I was eight when I realised that I was having thoughts towards guys," he explains. "By 12, I'd told my mum I needed to speak to a psychotherapist, but I didn't tell her why. She thought it was related to my dad's death.

"I saw more than 10 psychotherapists in my teenage years. Every time, I'd never say I was gay - I never allowed myself that - but that I was going through a phase and needed them to switch my thoughts towards women. They'd tell me they couldn't do that and I would have to accept myself. I'd just go on to another one.

"It was so tiring. All the energy I've put into changing sexuality... if only I could have put that into football, it would have been much better for my career, and for my mental health."

As his internal struggle continued, he would often hear anti-gay insults and attempts at jokes made around the academy. He would also search for answers in his faith but found only further confusion.

A standard slur was 'sale pédé', translating to 'dirty queer', as well as frequent uses of 'faggot'. No one knew Belgacem was wounded whenever these words were said. "For six years, I was hearing homophobic comments daily, and I was praying every night, saying 'please make me wake up straight - that's all I ask'.

"I got to 19, when I was playing with the reserves, and that's when I told my agent that I'd had enough and wanted to leave."

He is quick to stress that individual success in European football was by no means guaranteed. "But that's not even the point. To me, the point is that whatever the level I was going to play at, I should have been allowed to play at that level.

"If I'd been able to be in denial about being gay - and I'm not disrespecting anyone who has done this - I would have been able to play. Maybe Ligue 2, or if I could have, Ligue 1, or play in Belgium or Switzerland. I would have had the career.

"I should have been allowed, like any straight teenage kid, to try as hard as I could to turn pro. But homophobia did not let me."

"Without football, I'm helpless. The sport is my shield against all of my problems..."

- Ouissem Belgacem, writing in 'Farewell To Shame'

Belgacem could feel bitter about how his path diverged from those taken by several of his former Toulouse team-mates, but neither this interview nor his book leaves that impression. He writes about his teenage dilemma with sensitivity and self-awareness: "Do I fail at football because I carry a heavy secret, or does my secret become heavier because I'm failing at football?" Shame stalked him at every turn.

Only the psychotherapists he consulted, bound by confidentiality, were told his most personal piece of information. At the mosque, when he was able to pluck up the courage to even mention the topic to an imam, it was heavily coded - he would have concerns about something a cousin had said to him, for example.

If so-called 'conversion therapy' had been offered, he says he would have leapt at the chance. "If I'd known that existed, I would have asked for premium membership. I wanted to change so badly. In my religion, there's something in Arabic that we say, 'haram' - it's a sin.

"I was hearing bad stuff about gay people all the time. It was destroying me from inside. It was a nightmare."

In front of his friends, he would often wear a smile, laughing and joking to hide the distress he felt inside.

He eyed an escape - but football wasn't just about following his own dreams. It was also about being a breadwinner, securing a better life for his mother back home in Aix-en-Provence.

In the book, he sums up the Catch-22: "It's getting worse every day but without football, I'm helpless. The sport is my shield against all of my problems, and I don't know how to cope without it."

In a bid to salvage something from his talent, he changed agents and travelled to Tampa for a trial game watched by MLS clubs, impressing enough to secure a contract with the Colorado Rapids. Yet when he got to Denver, as a 20-year-old he was seen only as a development player. America was far from the promised land.

"I thought I was going to leave homophobia behind me, but it was there as well. In addition, being a Muslim in the States at the time was hard - I don't think it's very easy today even, but back then, the US was invading Iraq and Afghanistan. A lot of players were telling me, 'we need to fight these Muslim people. Why isn't France helping us invade these countries?'"

The racism and Islamophobia he faced added to his fatigue and he lost his enthusiasm for football itself. "How was I able to build myself as a man, as a person, while being in this toxic environment? No one could perform at their best level in those conditions. It's impossible."

Returning home would have meant failure, so he drifted instead to New York City and then London, where he would find his "liberation" - community, friendships, sometimes relationships, and purpose through his business studies which led to a well-paid position at a major utility company. Although he remained closeted at work, he glided between the "boxes" of British culture and over time, he no longer hated himself for being gay.

It transpired that Belgacem wasn't finished with football, though. With his job satisfaction diminishing, he was lured back into the sports industry by a brainwave to create the consultancy OnTrack, which was met with enthusiasm by former team-mates like Sissoko, now with Tottenham, and Capoue, who had moved to Watford from Spurs.

Belgacem's former Toulouse academy team-mates Etienne Capoue (top row, second right) and Moussa Sissoko (bottom row, right) went on to play for France

Belgacem's former Toulouse academy team-mates Etienne Capoue (top row, second right) and Moussa Sissoko (bottom row, right) went on to play for France

However, not only was it gruelling work just to get the company off the ground, but it brought back the emotional baggage of his youth. "I went back to homophobia but this time, it wasn't with teenagers, but with Premier League and Ligue 1 players.

"We'd go to restaurants in Mayfair and have dinner, and I'd hear the most horrific stuff about gay guys, and women as well. It's always such a soul-destroying moment when you hear that."

He describes a Sunday night in July 2016 at the Drama Park Lane club attached to the Hilton, a favourite haunt for celebrities. Andy Murray was there celebrating his second Wimbledon triumph. The group Belgacem was with included a Chelsea player who he had met several times previously and was keen to impress. "This player was like, 'oh Ouissem, I've seen you a few times now, but I've never seen you with a girl. What's wrong with you?'

"I forced myself that night to pick a girl and kiss her. Then I told everyone I was going home with her, and everybody was like, 'go for it man, that's the way'. We left the club and I pretended that I had a huge headache and that I couldn't take her home.

"She yelled at me - 'you made me go out of the club, now I'm going to have to queue again, how am I going to get back to the VIP area?' It was so painful. I was hurting others as well."

The decision to write his autobiography was made soon after, firmed up by a discovery that sounds even more emotionally damaging. Back home, family concerns had been growing. "I have four older sisters. I was so secretive that my mother asked a couple of them to call on me, to investigate me.

"She thought that maybe I was turning into a terrorist. That was a moment. How can she think that of me? But then I realised that I was doing everything I could to keep her at a distance. She was worried that maybe in the mosque in London, someone had brainwashed me."

He told each of his sisters about his sexuality - to varying degrees, they were supportive and understanding - and then he travelled home to tell his mother. "It went badly. She said some very strong words, that I should have been treated when I was a kid and that I was a 'curse' on the family. Because I was independent, I was able to absorb all her pain and her anger.

"We didn't speak for two years - but then she came back. She has a friend who lost her son and I think it made her realise how short life is.

"Now, she is amazing. She defends gay people on Facebook! To me, it proves two communities which you think are so far away - LGBT+ and Muslim - they can be reunited."

Belgacem likens it to a parent and child role reversal, in which he became the teacher. He recognised that he holds a unique position in football - an academy product no longer afraid to discuss what makes him different, someone who can share his experiences to benefit the current crop and their coaches.

He knows that's not enough to change a culture in which the harmful signals that are sent out by language and behaviour permeate a player's psyche over time. What would help a great deal, he says, is more vocal allyship from the star names that others seek to emulate. The responses to Belgacem's personal news from his old team-mates tell their own story.

"Since I came out to my friends, it's been fine. For some, it brought me closer to them and they told me I have 'big balls' - but it shouldn't be brave to be who you are nowadays. I can't believe we’re still having those discussions, it's so sad.

"As for some other players, I haven't received negative feedback, but they've put distance between us. I sense that they don't want to be associated. To me, that proves how necessary the message is."

Belgacem explains how OnTrack, the business he founded, helps to support footballers and athletes at different stages of their careers

Belgacem explains how OnTrack, the business he founded, helps to support footballers and athletes at different stages of their careers

On the weekend preceding the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia on May 17, French football authorities and clubs made an eye-catching attempt to communicate a commitment to LGBTQ+ inclusion.

Every Ligue 1 and Ligue 2 team sported rainbow-coloured shirt numbers while players held up pre-match banners reading 'Gay or straight, we all wear the same shirt'.

Paris Saint-Germain and Reims players before the Ligue 1 match at the Parc des Princes on May 16

Paris Saint-Germain and Reims players before the Ligue 1 match at the Parc des Princes on May 16

Belgacem supports the initiative, and others like it such as Rainbow Laces in the UK, but believes they can only start conversations, not provide solutions. The most effective communicators, he says, are the players themselves, through their words and actions. "Do we impose on them having to wear these shirts or do they really believe the message?

"Because if they are being forced, what's the point? There is none. If they really support the cause, why don't they make statements on that day against homophobia, on their Twitter or Instagram accounts?"

He expressed this view on one of his recent TV appearances and says the French Football Federation reacted defensively, as if they were being criticised. "The noise that my book is making in France is amazing from a public opinion perspective, but I can sense that the football industry is not supportive. I think they feel a bit embarrassed.

"But what kind of guys are we creating in these football academies in the UK, France, Spain or other countries, these professional football players? They are like leaders in terms of public opinion, followed by millions of people. They have to carry the right set of values.

"Nelson Mandela said it best - 'Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world'. The power and influence that players have now is huge. What they say is important - and what they don't say is important too."

PSG's Kylian Mbappe pictured in a rainbow-numbered jersey against Reims

PSG's Kylian Mbappe pictured in a rainbow-numbered jersey against Reims

Antoine Griezmann commented supportively in May 2019, a few months after Olivier Giroud told Le Figaro it would be "impossible" for male players who were gay to come out. "That didn't carry the right message. With that kind of mentality, we're never going to change anything.

"It's not good enough to say 'it is what it is'."

In June 2018, Collin Martin came out publicly while playing in MLS, while Englishman Thomas Beattie - who was a professional in the US, Canada, and Singapore before injury forced him to hang up his boots at the age of 29 - discussed his experiences of being gay in football at the end of Pride Month last year.

Belgacem fully appreciates that the prospect of intense media interest is a major concern for gay and bi players in the men's game, whether they are starting out, starting games regularly, or starting the next chapter of their careers.

He is convinced, however, that contentment awaits on the other side of that hurdle.

"It should be a non-event, but so long as we don't hear that story - that a player is gay and everybody's cool with it and he's just trying to make it like everyone else…

"Look, don't let others set barriers to your mind - you are great the way you are.

"If you feel like doing it, come out. I'll give you all the support that I can, and I think plenty of people are willing to give support as well.

"But if you don't feel like you're ready, don't. Hopefully we'll set the right conditions this coming year for you to be able to be yourself next year.

"Because nobody should have to hide who they are. The fundamental piece is to be happy."

'Mental strength' is one of the six pillars of OnTrack's mission statement for football and Belgacem now hopes his book will improve the game's understanding of the LGBTQ+ aspects of mental health.

"Nobody ever knew that I was gay, so all my suffering was lived from inside," he says.

"When you're in a changing room, if someone wants to make fun of someone else, he's going to mimic him in a very feminine way and everyone's going to laugh.

"Then you hear the coach - they need to be trained too. You don't have to use toxic masculinity. There are other ways to motivate players."

As a 17-year-old, in the Toulouse academy dormitory, Belgacem would struggle to sleep. "My consciousness and my subconscious are engaged in a relentless battle, day and night," he writes. "It's impossible to give my best in training.

"A vicious circle is in motion - the fear of being discovered, and the development of my sexuality."

On reflection, he realises that he could never end his "nightmare" on his own. He needed help from football itself.

Would that help be there for a player now? "I hope so. I want to challenge the system. This macho culture, it's so wrong.

"Basically what I'm trying to say is, it's 2021. People need to wake up."

Belgacem shares his advice for male footballers who are struggling with their sexuality

Belgacem shares his advice for male footballers who are struggling with their sexuality

'Farewell To Shame' by Ouissem Belgacem is published by Fayard, and it is hoped the book will be translated into English in the future.

Learn more about OnTrack Sport on their website.

Sky Sports is a member of TeamPride which supports Stonewall's Rainbow Laces campaign. Your story of being LGBT+ or an ally could help to make sport everyone's game. To discuss further, please contact us here.