Mental Health Awareness Week: Leon McKenzie on fight back from depression in the ring

The footballer-turned-boxer opens up about his battles with mental health issues after severe injury issues

Thursday 11 August 2022 10:44, UK

As part of Mental Health Awareness Week, Leon McKenzie recounts his struggles with depression, and how he fought back as a professional in the boxing ring.

McKenzie retired from football in 2013 after an 18-year career, which began at Crystal Palace in the 1990s and ended with a suicide attempt and severe injury problems.

He subsequently reinvented himself as a successful boxer, and of his 11 pro fights, McKenzie won eight, including a bout against Ivan Stupalo for the International Masters super middleweight title.

The 40-year-old is starring in a documentary "Ten Count", published by Redeeming Features Films, which looks at the mental health issues involved in sports stars.

Warning: Explicit content. Some readers may find the content upsetting

_____

There's no Pinocchio's nose with depression. There's no vivid signs from the outside. Explaining that, trying to make people understand that, is the least I can do with the experiences I've had.

The more normal depression becomes within society and the more people get used to hearing it, the more people are comfortable with speaking about it. That's progress.

_____

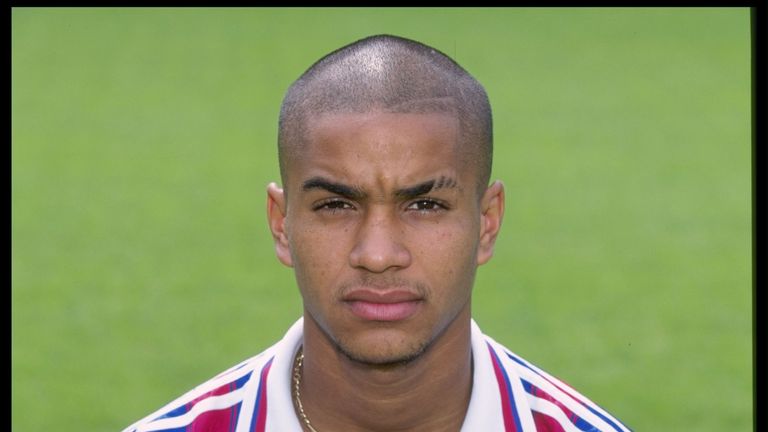

When I first signed for Crystal Palace from Sunday League, I knew I had talent and ability, but I was still raw and rough around the edges. I definitely had a lot to learn.

It was a bit daunting for me walking into Palace. Nobody ever showed me how to hold up the ball as a striker, how to shield off a defender, and I didn't know what a first touch was. I saw all the other kids as being ahead of me, more technical and intelligent in a footballing sense. I was on trial for six months, and it felt so long. But what I showed Palace was determination, heart, some ability, and every week I was improving.

They saw the progression every week, and they had no choice but to give me a contract. Steve Coppell was boss, and he really took to me. I worked so hard after training, and Coppell would tell me to work on my touch against a big wall, practise finishing, all of these little things. The next year I was flying.

I remember playing on a Saturday in the youth team. I scored a hat-trick in the first half and got taken off at half-time. I'm thinking: "What's going on here?" Coppell came up to me and said: "You're playing in the first team on Tuesday." I said: "Is this a joke?"

My debut came against Southend in the Coca Cola Cup in October 1995. I played really well, and to top it off I ended up scoring a goal I'd dreamt about for years. I signed a pro contract the next day. That was all down to Steve Coppell. He saw me, and gave me a big chance.

I'm still dreaming at this point, and after a couple years I'm thinking: "I'm actually a professional footballer, this is reality." I did have a lot of weight on my shoulders early doors and didn't score as many goals as I wanted for Palace. I was off the bench a lot, and he was breaking me in. I had the same kind of enthusiasm and impact on games as Ian Wright did. Wrighty was my footballing hero growing up.

I was at Palace for six years. Coppell left, a few people came and left, and managers either fancy you or they don't. I dropped down a couple of leagues to join Peterborough, and although my time there was disrupted by injury a lot, I had a decent three years. I was scoring one in every two, and that's where I really found my feet as a striker.

That was a massive part of me becoming Leon McKenzie, a recognised striker. But injuries always followed me in my career.

_____

I never really showed my true potential. My body never allowed me to be fully fit. Who knows what could have been? At Crystal Palace I'd snapped my cartilage in half, a career-threatening injury at 21 years old, and didn't know if I was going to play again. You try to stay positive, and psychologically I got through it. Coppell, for an entire season, allowed me to train only on a Friday, because of the swelling I would get in my knee. It was just a little five-a-side on a Friday, and I played on a Saturday.

I think if you asked a lot of my team-mates, I don't think many of them would say they wouldn't want me in their team. That's not to say I was the most gifted player, but they knew that when it was time to roll up my sleeves, get tough, I was there. And they knew I had a goal in me.

From Peterborough I moved onto Norwich. I'm a kid from Thornton Heath, South London. Although I did play a little bit in the Premier League as an 18-year-old at Palace, the odd sub appearance, it was very daunting for me at that age and it was still a huge dream for me to play regularly in the Premier League.

I made an impact at Norwich straight away in the second tier. I scored two on my debut against their rivals Ipswich, and set the mark there. We got promoted under Nigel Worthington into the Premier League, but I didn't start the first handful of games, until Mathias Svensson got injured.

I stepped in, and didn't come back out. I played alongside Dean Ashton, who I formed a brilliant partnership with. He's probably the best striker I played with. He's intelligent, the worst trainer I've seen, but when it came to matchday, he transformed into this intelligent, technical, classy footballer. We complimented each other.

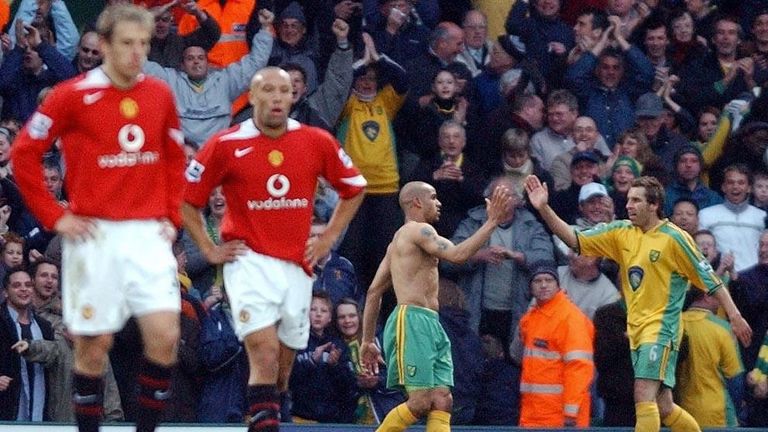

The goal against Manchester United was a moment in time that I'd reached against the odds. I'd had many injury problems even before this point. It was a crazy, beautiful moment.

But I found relegation with Norwich really hard. I felt that as a player I had found myself. If I'd have had one more season in the Premier League, with Dean Ashton, I really think I'd have had a better career. I'd just missed that boat when the big boys and proper, proper money came into football.

From Norwich I went to Coventry for three years, for just over £1m. It's a really fantastic club, a big club, but I played out in left midfield. All of my time there was adjusting to tracking full-backs and running up and down the line. I wanted to get into little areas to score goals, and this was a time where wingers were wingers, not inside forwards like they are now. Every time I said to managers at Coventry: "Please play me up front!" They'd say: "But you're playing so well out there!"

I had horrendous injuries at Cov; ruptured thigh and ruptured Achilles. I never really came back from that. The ruptured Achilles pretty much finished me. I had too long out, and then signed for Charlton after Coventry left me high and dry.

_____

Charlton is where my mind started deteriorating. I couldn't get back to the level I wanted to. I was desperate to do well at Charlton, another big club, but my body wouldn't allow me to.

I started a couple of games, coming off the bench here and there, but I was on the fringes of what I used to be. I think a lot of people knew that, and it was sad for me to carry. On the back of the ruptured Achilles my biomechanics had changed a lot, and all of these little things were going wrong with my body. I'm pulling my hamstring, my thigh, tearing my calf.

It was heart-breaking.

I loved football, I gave 110 per cent, I loved playing with my heart and scoring goals. When I started getting these injuries, that psychologically damaged me in a way that I still struggle to express.

The only way of trying to express it is this: I didn't want to live anymore.

When I was trying to get fit, in and out of the treatment and rehab, rehab, rehab. It was demoralising. I wasn't myself, I locked myself away a lot, left the training ground without much of a care.

There was a constant battle with fitness, let alone battling with form, and I was just praying I wouldn't get injured. I wasn't saying: "Please let me play well today." I was saying: "Please don't let me get hurt today." I was a shell of myself on the pitch. If I sprinted properly for that ball, slid in to tackle for that ball, play explosive like I usually would, there was a likeliness I would break down.

At Cov when I ruptured my Achilles against Birmingham, I broke down in tears. I knew I couldn't take much more of this. But at Charlton I was constantly breaking down.

I'd come back from a calf strain at Charlton, and in this particular training session I was absolutely on fire again. I was ripping defenders, scoring goals, and then out of nowhere. Bang.

I'd pulled my hamstring. Something happened inside me that day.

It was like something had left my spirit. Something had jumped out of my chest, and I couldn't take it anymore. I felt embarrassed, I didn't know who to look at. I put my head down, walked straight off the pitch to the treatment room and burst into tears.

When I look back and think about that day, there were so many people who walked past and didn't come in and say anything.

I couldn't cope anymore. The breakdown in my mind was tough. I called my mum that day after training, from the hotel in Bexleyheath. I was crying my eyes out, telling her I needed to retire and that I couldn't cope anymore. "I don't know what's wrong with my body!" I'd cry.

For a couple of months I had been collecting pills. In the hotel room, I shut my curtains and didn't come out of my room. I cried for the best part of four hours. I was in such a hole, I was trying to hold on but couldn't anymore. I was washing pills back with Jack Daniels, crying. It was a massive cry-out for help, but at the same time I had put the pills in my system.

So I called my dad, and told him I'd done something really bad. At that time I'm losing consciousness on the phone, can you imagine how my dad feels? I'm slurring my words and I'm about to pass out. Luckily, my Dad was about 15 minutes away. He could have been far, far away and nobody would have got to me. I may not have got through to my dad that day, but for whatever reason I did.

It was one of the worst times in my life. Everyone has their trigger, and the injury on that day was mine.

_____

I finished my football career in December 2011 and by February 2012 I was sent to prison after being involved in sending bogus letters to the police to avoid a driving ban. I was struggling at that time. I'm not a criminal, I've been an athlete all of my life.

But I wasn't happy within myself, and I believe all good people deserve happiness. I made a lot of bad mistakes, bad choices, and was very naïve. I wasn't thinking at all. I was giving people my speeding points… "Go on, please take them, I can't really deal with them right now." It was pathetic in many ways. It got blown up into such a big thing. The CPS wanted to make an example of me. What could I say? I'd broken the law, and everything was pointed on me.

They put me in an A-cat prison. I'd never been in trouble in my life. I went in with rapists, murderers and paedophiles, some of the worst people around. I'd been playing Premier League football not long before.

It was a reality check. I broke the law, and I take it on the chin. I put my head down and did my time. I was productive inside prison and, I didn't feel sorry for myself, got a job straight away as a cleaner, built a relationship with a few of the officers and started writing my book. I wrote and wrote and wrote, asking the officers questions, getting inside their brains.

I came out on a tag after four months, and things got worse. I went through my second divorce, and it was tough. I have five kids, and they are my world. I work hard each day for them.

Not waking up with my children every day - through my own bad choices and some things out of my hands - is a guilt I carry, and something I've always found hard.

_____

I'd retired from football, but went and played non-league for a bit. That was me enjoying football, with no pressure, and it was quite fun.

But financially things were hard. I was hit with a massive tax bill from my Coventry days, involving my agent and the club. It landed on me. I didn't understand it, I'd paid 40, 50 per cent tax all of my life, why was I getting hit with this? I was close to going bankrupt, and it feels never-ending, but you hold on and hold on. I financially lost everything, but also I lost my identity.

I'd come to this very dark place again, I had to move back in with my little sister in Woolwich, I had no car, no nothing. I'd lost everything.

People say: "Well, serves you right." But when you have a skill, like football, and all of a sudden you are essentially made redundant because of injury and you have to make a transition into something else, it's hard to take.

I had a routine, my way of life. I was now in my sister's room, in isolation, looking at the walls and crying, trying to fight. I said to myself: "I need to fight back."

Then boxing came in.

I'm a trier; I'll always, always try. I believe that when you try, you win.

I went to my dad and said: "I want to jump in the ring." He looked at me and just smiled. That smile was an indication of confidence, he didn't need to speak. He could just see in my eyes where I was at. For me it was a click. I started training and sparring during a very tough time for me. I was catching two buses and a train to get to Crystal Palace, at my Uncle Duke's gym. I was doing the graft.

It was like Rocky V. When it got to film five, Rocky had pretty much lost everything, and that's where I was at, but I didn't have my Adrian, it was just me. I was fighting back to hold on in life at the age of 35. I didn't want to go back to where I had been mentally.

Most people didn't know I had boxed all of my life, before football too. I was watching my dad and Duke throughout my life, so I knew the fundamentals around it. You can't jump into a pro boxing ring and do it well at 35 without that experience.

So on June 29, 2013 I made my professional debut. Eleven fights on, I'd won an International Masters Title, I fought for an English title and was a few points away from being champion of England at 38 years old. I can't complain with the way things went.

Boxing was such a buzz, very single-minded and all about you. All eyes are on you. In football, you can mask a few things, but there is nowhere to hide in boxing, which I found out in my third fight, a draw against Darren McKenna, a tough journeyman. He came to win, and it made me realise this was no easy ride.

I was progressing fast, and that's the thing with me, I learn very, very quickly. I fought for domestic titles, and that's some doing. Some people fight their whole life and don't get near to where I was, so to do that as my second career, at 38 years old. I rest my case.

_____

Depression will always be a part of my life, because it HAS been a part of my life. I hope you understand what I mean by that. But I choose to fight it. Although it may be impacting me one day, at some point in that day I'm going to change how it impacts me. I fight it. That's my motto.

You can't just wait for it to pass, keep productive, keep active, keep as positive as you can be. There are some days I don't want to get out of bed, but something will make me get out, something within myself will help me get out of bed.

But I strongly believe in counselling. When you get the right counsellor, it's a healing process. When you speak, it is therapeutic, and it comes from within. This is why I speak about my issues so much. Not only does it heal me in myself, I get great pleasure in seeing others listen to me speak and share my experiences. When they say: "Thank you," it is more rewarding to me than winning any fight or scoring any goal.

The amount of messages I've had, the amount of strangers who have reached out to me and said: "You inspire me and saved my life." I can't even explain to you what that does for me.

So I'm going to continue that until everyone gets it. That's my calling now. How I played football, and how I fought in the ring, I'm taking that same tenacity into this fight.

I could easily sit back and go through the motions in life, but for me there's nothing inspiring about that. I want to leave my legacy, I want my children to look at my life and think: "Wow."

_____

If you're really in that dark, dark place, go and speak to someone. Whether counselling or a family member, make sure you find it within yourself to reach out. That is the first step to progression.

You may not see it at that time, but that first admittance is the first step to you fighting back. When you do that, you're winning.

Don't feel a burden, particularly males, who have this pride and ego within themselves not to talk, to shut down and not show how weak you are. It's b******t.

As soon as you step forward and say: "I need help," to me you're a winner and a champion.

_____

Ten Count, launched by Redeeming Features films, is a documentary about Leon's journey, and the football to boxing transition.

It goes through the 10 rounds of my last fight, an epic battle, from round one, right to the end where I collapsed with exhaustion. It recounts my journey, including my depression and suicide attempts, and my battles. We've used other sportspeople who have suffered depression and raised the question: why are sportspeople so susceptible to mental health issues?

We want to raise awareness of this very, very important question. There are still so many people who just don't understand it.

_____

Leon McKenzie spoke with Sky Sports' Gerard Brand

If you are affected by these issues or want to talk, please contact the Samaritans on the free helpline 116 123, or visit the website.