The 10 Liverpools: Defining the Premier League champions

Invincibles? No. Treble-winners? No. But is this the most tactically-agile Premier League champion we've ever seen? Yes.

Saturday 27 June 2020 11:16, UK

Forget the unconventional crowning, the lack of celebrations. Liverpool have won the Premier League. Frankly, they've won it in every possible way.

With style and with grit. In the last minute and in the first minute. Against rivals and against parked buses. Through set pieces, through wide play, through the middle.

Defining them is impossible - their multiple personalities, their chameleon-like ability to adapt, have earned them an emotional first league title in 30 years.

Since August, Liverpool have been the best team in England. Here are the faces they've worn...

1. Bounceback Liverpool

Fact and feeling didn't match at the end of the 2018/19 season. The fact is, Liverpool lost just one of their 38 games and earned 97 points. That's enough to win 25 of the previous 26 Premier League titles.

But the feeling was different. They weren't outstanding, because City, a point better, were. Liverpool were close, but no cigar. As good as it will get. "Second place is first loser" and all that.

Their first step on the road to recovery was Madrid. A Champions League final - not a bad way to instil a winning feeling. Jurgen Klopp gagged Tottenham and led Liverpool to silverware, but a full summer and full season were to come.

To reproduce, recycle, go again would have tested not only Klopp's man-management skills, but the ceiling of his own belief. Liverpool's fulcrum of feeling, their captain of character, had to find a way of convincing his team to do better than their best.

"If you see whatever happens to you in life as the only chance you ever had, I feel a bit for you, to be honest. There's a lot to come, a lot of years and it's all about you, what you do with it."

It sounds like a passage from a self-help book. But that's Klopp in his press conference on the final day of the 2018/19 Premier League season.

It would have been easy for Liverpool to gaze outwards at City and conclude that their only hope was for Pep Guardiola's world beaters to get worse. That happened, of course it did, but the Liverpool that swooped in were a new beast. Klopp's emotion on Thursday night said it all: this was an enormous comeback.

2. High-line Liverpool

It wasn't exactly screaming out to be fixed. Liverpool's change of tack came in a defence that had conceded 22 goals in 38 games.

Suddenly Liverpool's defensive line pushed higher, a tweak that had an impact further forward.

After 22 minutes of their first fixture, Norwich had breached Liverpool's offside trap three times. There was concern: why fix it if it isn't broken?

"I don't like the high line and I think they've been lucky and fortunate at different times this season to get away with it," said Jamie Carragher early this season.

As time went by, the benefits of Klopp's forward-thinking tweak were evident. Liverpool made the pitch small and almost exclusively in their opponents' half: a mobile back four meant long balls out for relief were often dealt with via a simple foot race. And whichever way you look at it, the introduction of VAR eradicated incorrect offside calls. No, it actually did.

But what about the low blocks? Those parked buses that led to seven draws in 2018/19? The high line gave Jordan Henderson a permit to join attacks, and the full-backs to become out-and-out wingers.

Fabinho, now one of the best central midfielders in world football, hoovered up most of the mess before it even reached the centre-halves, so Liverpool played the numbers game up the pitch. They simply marinated the opposition half with players.

It was often pinball, chaos in tight areas, but Liverpool always prevailed because, well, they always had more quality. In football, it's as failsafe as you can get.

3. Last-minute Liverpool

Villa Park, November 2.

A goal down to Villa with three minutes remaining, Andrew Robertson scores to seemingly grab a point. Liverpool have been nowhere near their best.

Forget the celebrations. The Scot tears away from goal with more pace than with which he arrived, waving his arms for teammates to join him back at base, the centre circle.

There's no settling, no "Let's get out of here." They smell blood, weakness, and have a few minutes to turn one point into three. Moments later, Liverpool have their winner through Sadio Mane.

In the last 10 minutes of Premier League games, Liverpool have earned 12 points. Many call this trait luck, but that in itself is an oxymoron. If it's a trait, how can it be luck? Like Manchester United in '99, Liverpool made their own luck through persistence.

Pep Guardiola would agree. "My son and my daughter, all the time when [Liverpool] win in the last minutes, ask me how lucky they are," the City boss said in November. "I say at the time: 'It's not lucky'. What Liverpool has done last season and this season many, many times is because they have this incredible quality and this incredible talent to fight until the end."

United had Fergie Time. Liverpool have Kloppage Time.

4. Lucky Liverpool

Yes, you do make your own luck. Liverpool have curated their own again and again, and they would still be clear at the top of the Premier League even if luck had been against them.

But that's not to deny that fortune has favoured Klopp's side in parts this season. Even the German admitted it after a 95th-minute victory over Leicester in October: "Without luck, we cannot win the amount of games we have won."

That win over Leicester at Anfield came courtesy of James Milner's penalty after Sadio Mane had been brought down by Marc Albrighton. It's undeniable Mane made the most of it.

Then there was the flailing arm. You've seen the slo-mo a hundred times. Did Bernardo Silva's deflected cross hit Trent Alexander-Arnold's hand in Liverpool's win over Man City in November? Liverpool went up the other end and did what the authorities feared might happen with the introduction of VAR: they scored in the same passage of play.

City erupted, Pep had hot lava in his veins. But it stood; Liverpool had their tails up and went eight points clear.

The 1-0 win over Wolves in late December was the campaign lead for anti-VAR sentiment, and an important early-season win at Sheffield United came via Dean Henderson's howler and the greasiest of gloves.

But it doesn't have to be one thing or the other: you can experience bags of luck and still thoroughly deserve to win a title. Luckypool? It's nothing more than a defence mechanism for those who have struggled to come to terms with their dominance.

5. Trent and Robertson's Liverpool

Bizarrely, Liverpool's chief playmakers are their full-backs. One came from the academy. One was £7m from Hull. Both have been coached into phenomenal players.

Take Andrew Robertson and Trent Alexander-Arnold out of the side, and you lose Liverpool's main attacking threat, their symmetry, and a large chunk of their game plan.

In theory, it's quite simple. Liverpool often build their attacks narrow, drawing opposition in and leaving space out wide. Enter Trent and Robertson, with a range of delivery any attack-minded player would be pleased with, and endless engines. Over-committing full-backs? No, because Klopp gives them license.

If that move isn't on, there's another way.

Rather than shuffling the ball across one-by-one to get from one wing to another, the trait of a traditional possession-based side, the full-backs routinely go directly to each other. Those long diagonals are often the trademark to any Liverpool attack; defences are stretched faster and often snap, leaving more holes for the three forwards to occupy.

A risky ball to play? Again, no, because Klopp allows for it.

It's straightforward, but so difficult to stop. Twenty-three assists combined last season, and 20 this term suggests it won't slow down as long as quality in the middle remains. Put a man on the full-backs and you leave the midfield unpoliced.

There's no winning. Liverpool have it covered.

6. Possession Liverpool

Klopp's tactical dexterity doesn't stop there. Liverpool's motor takes many roads to goal, and the most recent discovery is the furthest departure to date from the heavy metal label we often stick on Klopp.

Since the beginning of winter, possession became more a part of Liverpool's game. Before the win at Bournemouth on December 7, Liverpool were averaging 2.33 passes per possession and just over 500 passes per game, but since that has drastically risen to 3.38 passes per possession and 694 passes per 90 minutes.

A forced move, or something more conscious from Klopp? You'd think the latter. As it became apparent that Liverpool were unstoppable, the team to beat, oppositions dropped deeper. That means more time on the ball and an increased need for patience. Liverpool's quality almost always prevailed.

Then there's the idea of resting while playing. More time on the ball means less time running after it; and Klopp seems happy to park that tsunami style to catch a breather. It is indeed interesting that this change of style came at the start of a hectic winter period Klopp had so publicly criticised.

Rest is part of Liverpool's work. Three of the back four - Alexander-Arnold, Virgil van Dijk, Robertson - lead the Premier League in touches, allowing those in front of them to breathe.

In particular, Van Dijk is the conductor. You'll see him stood dead straight, foot on the ball for a few seconds to bring calm, an arm outstretched as he manoeuvres those in front. Forwards daren't go near him - he's too good to force a mistake. Maybe he'll ping it into midfield to start an attack, but he's just as likely to sit tight.

It's another example of Liverpool's adaptability. Invincibles? No. Treble-winners? No. But is this the most tactically-agile Premier League champion we've ever seen? Yes.

7. Durable Liverpool

On the face of it, Liverpool had injury issues this season. Joel Matip was unavailable for 13 Premier League games; Alisson, Naby Keita and Fabinho missed eight apiece through injury; James Milner seven.

But dig a little deeper. Though controversial at times, Klopp's squad management has been superb, and his key players have almost always been available.

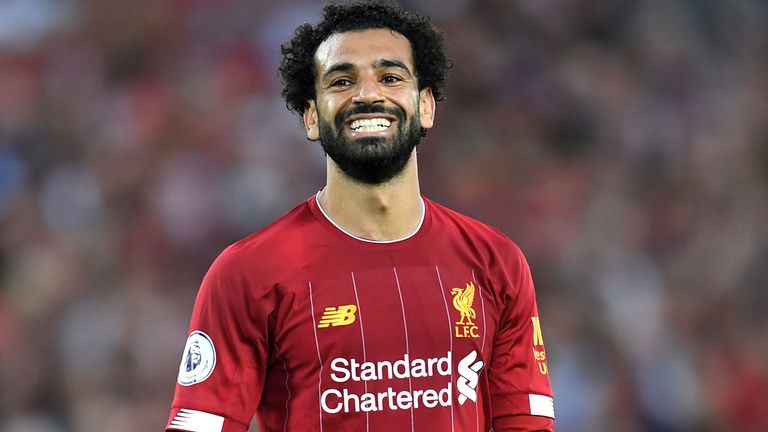

Henderson: three Premier League games missed through injury. Salah: three. Mane: two. Andrew Robertson: one. Van Dijk: zero. Alexander-Arnold: zero. Roberto Firmino: zero. Gini Wijnaldum: zero.

It hasn't been the same for Liverpool's rivals. At Manchester City, Aymeric Laporte (19 games) and Leroy Sane (entire season before restart) were missing; Manchester United have been without Paul Pogba (22), Luke Shaw (10), Scott McTominay (7), Marcus Rashford (7) and Anthony Martial (6) for large chunks.

Tottenham have had Hugo Lloris (14), Erik Lamela (9), Moussa Sissoko (8) and of course Harry Kane (9) missing, while Chelsea had to get by without Antonio Rudiger (15), Ruben Loftus-Cheek (entire season before restart), Callum Hudson-Odoi (11), N'Golo Kante (9) and Christian Pulisic (9).

So, fortunate Liverpool again? Not exactly. Liverpool's reward for success was more games. The Club World Cup added a layer of toil, but Klopp has been both savvy and stubborn with his squad use this season.

It wasn't always this way.

"Liverpool manager Klopp has run his players into the ground during pre-season," said Raymond Verheijen in 2017, the Dutch fitness coach who has worked with Barcelona, Chelsea, Bayern Munich and Wales. "Consequently, players cannot perform during an entire season."

Those times have changed, and with the help of two former Bayern Munich employees. Fitness coach Andreas Kornmayer and nutritionist Mona Nemmer have contributed to a transformation in Liverpool's fitness levels over the course of the season, and that post-Christmas slump so synonymous with Klopp is now a thing of the past.

In Klopp's first three seasons, Liverpool won just 33 per cent of their January games. In the previous two Januarys, they've won 66 per cent. It's another example of that incessant culture of improvement. In this Klopp regime at Anfield, no stone goes unturned.

8. Set-piece Liverpool

Liverpool's potency at set pieces at both ends of the pitch was decidedly mid-table before the summer of 2018. The Champions League final defeat in Kiev prompted much mirror-gazing and subsequent changes, but Klopp's increased focus on dead balls was among the most important.

This season, that has continued.

Think of the very best Premier League teams over the years, and you don't often think of set-piece prowess. But Klopp, along with the work of assistants Pep Lijnders and Peter Krawietz, wanted to maximise all areas of the team's CV, and the set piece is an unavoidably large chunk of any match.

There was no scoffing at Melwood. They even brought in a throw-in coach.

The result? 12 set-piece goals scored (2nd in Premier League) and just five conceded (18th). Last season, they scored 20 (1st) and conceded eight (19th).

Many deadlock-breakers and match-winners have come from Liverpool's deadly set piece. See: Joel Matip's opener against Arsenal in August, Trent Alexander-Arnold at Chelsea in September, Van Dijk's first and second against Brighton in November, then his opener vs Man Utd in January, plus Jordan Henderson at Wolves a few days later. The winners - Mane at Villa, Roberto Firmino at Palace in November - were part of chaotic sieges on goal from corners.

But how do they do it? It helps having a world-class delivery in Alexander-Arnold, and giants in Matip and Van Dijk in both boxes. Put in the right area and attack, correct?

According to Klopp, it's carefully crafted for each game.

"The most important thing is we always have routines for the next game," Klopp explained post-match. "That is all up to Pete Krawietz and the analysis boys, they put a lot of effort in that."

9. Big game Liverpool

Liverpool barely lost against a top-six side when Klopp first arrived in England. They were bold and often blitzed in short spurts. But in finals, when it really mattered, they fell short.

Klopp, the cup final 'bottler' to some, changed tack in the 2019 Champions League final. Abandoning the onslaught, Liverpool simply stopped Tottenham in every sense. Henderson and Fabinho played deeper, Spurs had no space to work in, and the cup was won.

The style surprised many, and gave Liverpool a template to take into big games this season. Against Manchester United home and away, the exhibition of discipline and prudence was put on full display.

October's 1-1 draw at Old Trafford was the most cautious Liverpool have played in five years under Klopp, and the 2-0 win at Anfield was about scoring early, not obsessing over possession, sitting slightly deeper and picking off late on. These two games in particular - against a United side who routinely upped their game for their rivals - signified a shift in Liverpool's big-game thinking.

In dropping deeper, Henderson, Fabinho and Wijnaldum act as an extra line of defence to allow the full-backs to join the attack on the break. It's disciplined, and means that if creativity in midfield is absent, it's simply available elsewhere.

Are Liverpool now less exciting to watch in big games? Perhaps. But Klopp, no longer the bottler, prefers silverware to entertainment.

10. Room-for-improvement Liverpool

So. They've won the Premier League title. They're likely to break the points record and wins record. Their nearest challengers are a blurry 23 points behind.

If that wasn't scary enough for Liverpool's rivals, the fact is they've also got room for improvement.

Yes, this Liverpool team can get even better.

They've won games they shouldn't have this season. They've won games uncomfortably and awkwardly. They've been underwhelming in large chunks against lesser teams at Anfield.

And yes, I can hear you saying: "The sign of champions," but Klopp won't dismiss uneasy performances as some sort of fate attached to successful sides. For him, it's performance and result, not one or the other.

And the argument that Liverpool were more impressive in 2018/19 should not be disregarded. In parts they very much were.

So, how do they improve? Quality back-up for the front three should take priority, but that comes with difficulties. Takumi Minamino is a work in progress, and Divock Origi, though adored for last season's heroics, lacks that artistry the front three have in buckets.

Any forward player coming into Anfield knows they must shift Mane, Salah and Firmino for minutes, all 28 and in their prime. Klopp will also be careful to balance competition for places with morale. That will be a challenge in the coming window, and may explain why Timo Werner passed them by.

Andrew Robertson needs better cover, and though the midfield don't necessarily rely on creativity - they are pistons for the engine - any tweak in style in the coming seasons may require more wit.

It doesn't fit the narrative, but this incredible Liverpool side have work to do this summer. You didn't expect Klopp to just sit back and admire the job, did you?